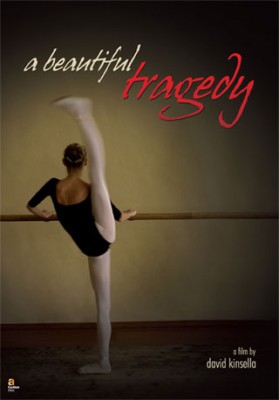

A striking animation opens David Kinsella‘s 2007 film, A Beautiful Tragedy.

“Once upon a time,” it begins, “there lived a woman. She dreamed of becoming a ballerina but her dreams never came true… and then she gave birth to a little girl, and decided that the babe would become a ballet dancer.”

The girl is put on a factory conveyor and fed to the mouth of a waiting monster, the ballet school. There she practices. Anguished, she sees an overweight version of her own image in the mirror.

The young girl is then 15-year-old, 5′ 3″ and 81.4lb, Oksana Skorik. The film follows her throughout the 2004/2005 school year at the Perm State Choreographic School, one of the most prestigious ballet academies in Russia. Though plot and perspective are blatantly revealed in the grotesque and dramatic opening, Kinsella has indeed created a beautiful and devastating film from which it’s difficult to tear your eyes away.

“Beauty demands sacrifices,” explains one of the Perm instructors as she speaks to the camera about the difficult profession of ballet. Yet the statement doesn’t wave away some of the more unsettling aspects of this film: That students are sent mixed messages about weight. That the young dancers have etched expressions of anxiety as they suffer verbal abuse from instructors along with the internal and external pressures of class. That some, like Oksana, seem completely unable to see themselves realistically, obsessing over food, weight, and minute distinctions or features of the body.

Near the end of the 60 minute film, Oksana is preparing for her final classical exam for the year. She writes letters home detailing her fears that she’ll be lucky to score a 2. She makes a list of her faults and compares herself to the other girls. Following the exam she writes again, indicating that she’s done poorly. When results are announced, her score is a 4+, the highest or at least among the best in the class.

As the news is delivered, Oksana is in tears, though it’s unclear whether relief or other emotions are at work as her instructor congratulates her on not doing anything stupid, glorifies the quality of her legs, and suggests that the others must make the best of their own “crooked stumps.” Is the teacher intentionally aggravating existing jealousies among the classmates? Is she aware that Oksana has felt alone and ostracized all year? It’s hard to say.

Throughout the documentary, Kinsella is illustrating a point of view on anorexia and unrealistic weight expectations in Russian ballet. I am still uncertain if, or to what degree his bias is unfair, however. The film is entirely in Russian and subtitled for an English-speaking audience. Though Oksana is not alone in having distorted views of weight and eating, some students seem to be faring better in this environment. So is this the norm or are the filmmaker’s quick and selective cuts limiting or even skewing the scope of the tragedy?

Is being disturbed by an instructor aggressively thumping a student’s rib cage into place, calling an underling and idiot, or shoving a pupil from her position in the room evidence of my own cultural bias about what is acceptable in a classroom? Perhaps, but it doesn’t make it right.

Is the film attempting to show only the worst side of Perm’s elite ballet school? I don’t know but nothing incriminating was captured via hidden cameras that I could tell so, if the school’s bad side is displayed, it was done so knowingly.

Questionable instruction methods or agendas aside, this is really Oksana’s story. She is a sullen and homesick teenager. The problems with other students and resulting loneliness she experiences are at least in part the consequences of her age-appropriate angst. Under extreme pressure from all sides, it is no wonder that it’s her own body with which she wages a war of control. She is “fighting against her own nature.” Oksana says it herself in the film’s epilogue.

This postscript, apparently an addition to the original cut and captured two years later on the threshold of Oksana’s graduation from the academy, shows a more mature and healthier-looking but thin young woman who confesses her former battles with anorexia. She is proud to have come out the other side of her troubles and looking forward to a future in dance. She will spend it at the Mariinsky Theatre – Oksana [Oxana] is currently a coryphée in the Kirov – The Ballet Company of the Mariinsky.

It is a surprisingly hopeful ending for a tragedy. (If you’re looking for casualties in the quest for perfection, I suppose there’s always Black Swan.)

Still, Oksana’s final reflections recall a statement made earlier in the film by Perm Ballet professional and Oksana’s kinder, gentler teacher, Natalia Moiseyeva. Speaking of her own trials as a student, she muses, “I think this profession’s for people with masochist tendencies. You’re always forcing yourself. It hurts, and you even get a rush for overcoming that. …At the end of the day, you get satisfaction from the result.”

True for all ballet dancers? You decide, but it’s difficult to make one’s way through A Beautiful Tragedy without wondering at least once if beauty truly is worth the sacrifice.

Have you seen A Beautiful Tragedy? What were your reactions to the film?

Nichelle Suzanne is a writer specializing in dance and online content. She is also a dance instructor with over 20 years experience teaching in dance studios, community programs, and colleges. She began Dance Advantage in 2008, equipped with a passion for movement education and an intuitive sense that a blog could bring dancers together. As a Houston-based dance writer, Nichelle covers dance performance for Dance Source Houston, Arts+Culture Texas, and other publications. She is a leader in social media within the dance community and has presented on blogging for dance organizations, including Dance/USA. Nichelle provides web consulting and writing services for dancers, dance schools and studios, and those beyond the dance world. Read Nichelle’s posts.