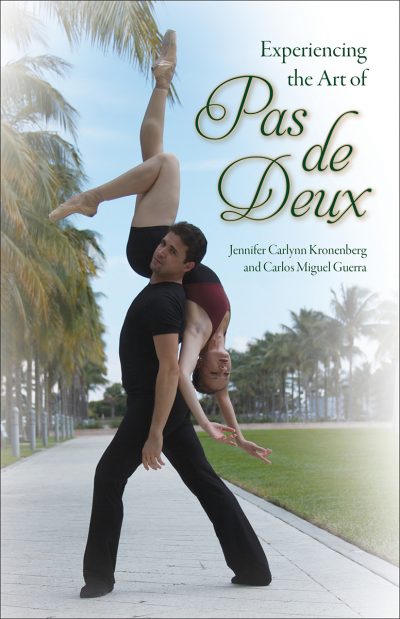

Jennifer Carlynn Kronenberg and Carlos Miguel Guerra, partners on-stage and off, present a book with a thorough understanding of the needs of both sides of a unique ballet partnership: the ballerina and her cavalier. This is a detailed guide that not only offers very practical advice to dancers (or “ladies and gentlemen” as the couple gallantly refers to partners) but also a generous helping of historical context and personal philosophy. It’s a winning formula for readers, whether they are professional ballet dancers, teachers or students.

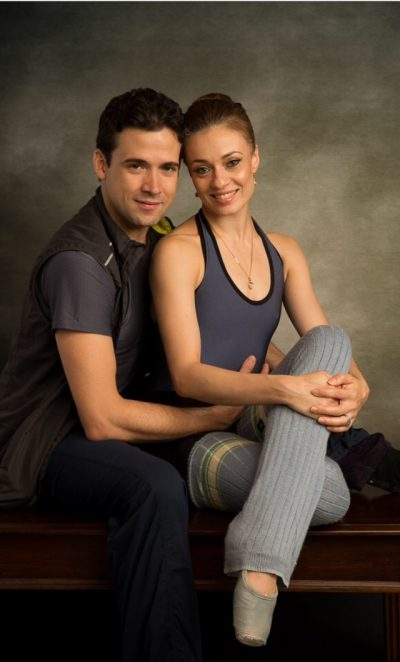

First a brief history of Kronenberg and Guerra: they met – naturally and utterly romantically – when they were partnered at Miami City Ballet. During rehearsal for a pas de deux from “Nine Sinatra Songs” which Twyla Tharp was setting on MCB, Tharp herself commented on the chemistry Kronenberg and Guerra seemed to have, even though they were not dating at the time. They write that romance often blossoms in on-stage partnering and couples, regardless of their personal relationship, would do well to treat that partnership as if it were a marriage, with all the joys and pains, the compromise and connection that a marriage entails.

As for pas de deux itself, the authors provide historical context for the tradition, dating all the way back to European social dances of the early 18th Century. These partnered dances primarily consisted of couples dancing closely together, doing the same choreographed steps, and occasionally holding hands. Eventually, this evolved into more dramatic scenarios with each dancer playing a “role” in service of a story being told for an audience.

The current form we see today can be traced to choreographer Marius Petipa in the early 19th Century. Many credit him with creating the Grand Pas de Deux which typically features a partnered adagio, followed by male and female variations to showcase each of the dancers, and finally a spectacular coda with both dancers. While these pas de deux are constructed as part of the story ballet, be it Sleeping Beauty or Swan Lake or Nutcracker, the dancers are not really portraying characters or dancing with each other as the characters they are playing. This is why many Grand pas, which are feats of beauty and ability and are usually extraordinarily challenging, are often performed on their own without the surrounding story ballet.

While the authors frequently refer to same-sex partnering in contemporary ballet and modern dance and include some guidance for such partnerships, the book is aimed squarely at classical pas de deux, which is a female dancer supported by a male dancer. But if you think the authors subscribe to a theory of “male dominated” dance, think again. Both male and female partners have their own responsibilities in pas de deux, from physical preparation like core strengthening and cross-training to reframing one’s mental mindset.

Philosophy and guidance, based on the couple’s personal experience, are two areas where this book shines.

“There is a genuinely comforting feeling to know that in dancing a pas de deux you are never alone. There is always someone’s hand outstretched ready to accept yours and someone’s eyes waiting anxiously to meet your gaze.” (p. 154)

As a student of dance, I absolutely loved their references to dancers as “ladies” and “gentlemen.” It not only reminds us of the roots of ballet in court dances, it also reminds dancers of the need to be respectful of each other. This includes such obvious kindnesses as wearing deodorant, sucking on a breath mint before rehearsal and limiting use of colognes and perfumes, but also the not-so-obvious such as not placing blame on your partner for a failed lift, trusting yourself and your partner, and leaving disagreements outside the studio.

As a teacher, I gobbled up all of their tips. After so many years of partnership, with others as well as themselves, Kronenberg and Guerra have had successes and failures, and they are eager to share both. As an example of the former, their casting as Romeo and Juliet at Miami City Ballet was a highlight of their professional careers, but one they had to fight hard for. The proprietor of the John Cranko Trust, Reid Anderson, who was setting the dance on the company, was reluctant to cast a married couple but they convinced him to give them a chance. Examination of the latter, such as a timing misstep during a rehearsal for Paul Taylor’s Piazzola Caldera that resulted in a head injury for Guerra, provides fair warning to dancers that pas de deux is not to be taken lightly. It is very serious business and calls for a solid connection and honest communication between the partners.

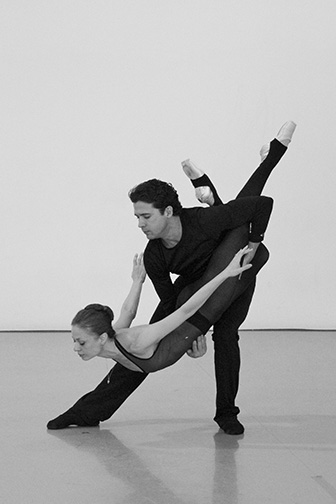

After the authors spend a chapter highlighting some famous partnerships over the years – Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gelsey Kirkland, Peter Martins and Suzanne Farrell, Jock Soto and Wendy Whelan, among others – they get to the practical matter of “how-to.” With incredibly detailed instructions and photos, the couple demonstrate how to accomplish certain lifts, poses and turns. Each one is graded as “simple,” “intermediate,” or “advanced” but truly, they should be attempted by dancers who are already familiar with partnering. Even the lifts identified as the easiest will be challenging. The authors’ tips should help, such as these in regards to lifts:

- “A lady must try to push off the ground toward her partner, not away from him.” (p. 100)

- “Contracting the abdominals and tightening the core will make a dancer more compact, allowing her to be more easily lifted.” (p. 100)

- “A gentleman must never squeeze the lady for added security.” (p. 101)

- “Partners should try to time their actions so that they will lift with the lady’s momentum rather than against it.” (p. 102)

Off-Balance Lean Back (credit Leigh Esty Photos)

For many of the lifts and turns, there are accompanying videos which can be accessed immediately using the QR code on the page. For example, when I wanted to look more closely at the Ballet Shoulder Sit From a Running Start (p. 124) on my iPhone 5s, I loaded a free app called QR Quick Scan. Once opened, I aimed the camera at the QR code on the page and the app gave me a URL which took me to a very well-designed and edited video of Kronenberg and Guerra demonstrating the lift in a studio setting. While not every lift and turn has a separate QR code, many do and they provide an abundance of technical tips that complement the book.

The book may be purchased online at Amazon. Or through the University Press of Florida’s website.

About the authors: Jennifer Carlynn Kronenberg is a former principal dancer with the Miami City Ballet. She has conducted master classes for Ballet Chicago and Ballet de Monterrey, among other companies and schools, and is the author of So, You Want to Be a Ballet Dancer? Carlos Miguel Guerra is a former principal dancer with the Miami City Ballet. He studied and worked with Fernando Alonso in Cuba, Ivan Nagy in Chile, and Edward Villella in Miami.

Leigh Purtill is a ballet instructor and choreographer in Los Angeles where she lives with her husband and charming poodle. She received her master’s degree in Film Production from Boston University and her bachelor’s in Anthropology and Dance from Mount Holyoke College. She is the author of four young adult novels from Penguin and HarperCollins. She is the artistic director of the Leigh Purtill Ballet Company, a nonprofit amateur ballet company for adults and she teaches ballet and jazz to adults both in person and online, Leigh Purtill Ballet. Read Leigh’s posts.