Welcome back! I hope everyone enjoyed Part 1 of Tap Is Music (And I Can Prove It). We’re halfway there so read on, true believers!

So far we have covered how tap dancers can control their dynamics to make steps loud and soft and how they can sustain certain “notes”. This article will focus on pitch and timbre, completing our comparison of tap to the four elements of musical tone.

Pitch

What is pitch and how do we measure for it?

Pitch is the relative highness or lowness of a note. Notes of different pitches have distinctive sound wave frequencies that are measured by the number of complete waves or cycles per second. It is easy to determine changes in pitch simply by looking at its waveform.

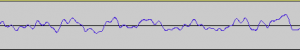

For example, this is the waveform of C1, the lowest C note on my piano:

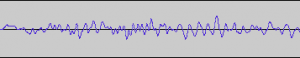

And here is the highest C note that my piano plays, C6:

It is plain to see that the lower pitch contains far fewer waves than the higher pitch. The crests of the waves are spaced much farther apart than the high C’s, which are jagged and very close together.

You Can Tune A Tap Shoe, But You Can’t Tuna Fish!

This simple test can be applied to tap dance, and it is possible to tell different steps apart based solely on their waveform.

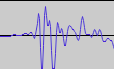

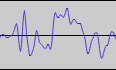

Take the flat heel and the flat toe taps. The heel of the tap shoe generally produces a much deeper tone than the thinner front tap. Using my Dancing Fair GS-1s, I recorded a single tap on both the heel and the toe. Can you tell which of these two waveforms is the heel and which is the toe?

The first wave form belongs to the toe, with its tight and narrow ridges, and the second waveform belongs to the heel, with large and loping strides from one wave to the next.

Variables

Here is a list of some of the variables that will alter a tap dancer’s sound:

The Tap Shoes – Sole Thickness (Single, Double, Triple)

The Taps – Size, Weight, Thickness

The Dancer – Center Of Gravity, Weight

The Wood Floor – Wood Type, Grain, Coating (Stain/Finish, Polyurethane/Epoxy)

That’s, like, a bazillion different combinations, and that’s not even factoring in variations in weight and posture, different species of wood, or the different brands of floor coating, among other things. The pitch possibilities are positively infinite!

Calculating Permutations? Is that the one starring Ben Affleck?

Timbre

Timbre is the unique vibrational form that is produced by the particular combination of the strong harmonics of an instrument. This is also what enables us to tell one instrument from another and why an oboe sounds like an oboe… because of its timbre. With regards to an orchestra, it is the combined timbre of all those instruments together that creates an audible experience that ranks among the greatest pleasures on earth, and why the nearly 100 members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra has a much richer sound than my old four-member band from high school.

That and talent.

It is the unique timbre of tap dance that is its greatest musical strength. People respond to the sounds of tap dancing like nothing else on earth – the warm sound of a clean strike against a wood floor, the scrape of sharp metal against the grain. I could imagine the people of Europe and the Middle East as early as 1200BC, during the iron age, perking their ears as the first metal tools beat against wooden constructs. Besides tap dance, today we still enjoy the sound of metal on wood through vibraphones, drum cymbals, and latin instruments like the Guiro and Cabasas.

Less Def Tone, More Tone Deaf

What keeps tap as being immediately recognizable as an instrument is its greatest musical weakness. While tap dancers make “def” rhythms, if I understand the vernacular jive of kids these days, tap dance has no tone.

When we hear an instrument play a tone, or note, what we are really hearing is a series of tones. A tone is a sound that has a definite recognizable quality. What we hear as a note, like G or C#, is fundemental frequency, the tone with the lowest frequency. The other higher-frequencies, called harmonics, are covered up by the fundamental frequency and made imperceptible, thus giving the listener the impression of a single note. (There are ways to hear the harmonics, however.)

When a tap shoe strikes the floor there is no discernible fundamental frequency. What we get is a cluster of similar tones that create what scientists like to call “noise.” The pitch is still discernible, but it would be impossible for a tap dancer to play a specific musical note, interval, or chord.

Thus the “Tristan Chord” is lost to tap dancers. Really.

This puts tap dance in the realm of unpitched instruments, which are instruments with indefinite pitch and no definite tone, and in league with instruments like the tambourine, most drums and the cowbell. Just because an instrument is unpitched doesn’t make it any less awesome!

Tap Is Music

It is through these four elements – dynamics, sustain, pitch and timbre – that we perceive the physical and subjective qualities of music.

The art form of American tap dance conforms to all of these elements, and then some. Few percussive dance forms match tap’s rhythmic versatility. Save for some types of body drumming, I am aware of no other percussive dance form that is as audibly adaptable as tap dance.

If tap dance contains all the elements of music then I will have to conclude that tap IS music. You may have heard that before, but I can prove it.

Tristan Bruns has studied the art form of tap dance with Donna Johnson, Ted Levy, Lane Alexander and Martin “Tre” Dumas and has a BA in Music from Columbia College Chicago. Tristan has been an ensemble member of such Chicago tap companies as BAM!, The Cartier Collective and MADD Rhythms. Tristan currently produces his own work through his company, TapMan Productions, LLC, which includes the performance ensemble The Tapmen and the tap and guitar “band” of The Condescending Heroes.