Sparkling tulle and satin pointe shoes, a music-box melody, and the status of ballet royalty–the Sugar Plum Fairy is the ultimate tutu and tiara role.

But let’s take a look at the REAL story behind The Nutcracker’s most famous and enchanting character…

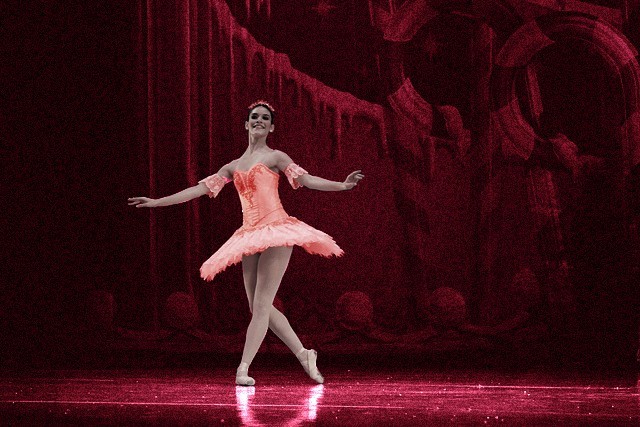

Photo by Gabriel Saldana. Licensed under CC Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic. [Changes to photo: filters added]

An Inspired Infiltration of Sweets

Ironically, the Sugar Plum Fairy is not found in the original E.T.A. Hoffman story Nutcracker and Mouse King or in Alexandre’s Dumas’s The Tale of the Nutcracker, the retelling on which the ballet’s first libretto was based.

However, the lush descriptions of the realm of sweets in both versions could inspire many different balletic personifications of candy. Here’s a snippet from Dumas:

“All the surrounding houses were sugar candy, with galleries upon galleries. And at the center of the square, in the in the shape of an obelisk, there was a gigantic brioche, in the midst of which four fountains bubbled away: lemonade, orangeade, orgeat, and currant syrup. As for the basins, they were filled with whipped cream […]” (1)

Additionally, during the era in which The Nutcracker ballet was developed, the term “sugar plum” referred not only to a specific sweet, but, as author Samira Kawash points out, was also “the universal signifier everything sweet and delectable and lovely.” She further explains that the actual “sugar plums” of those days were, in fact, mostly sugar and no plum. They were treats in the category of “comfit”– candy created by layering sugar coating over a seed or nut center. She cites Jordan Almonds as a modern-day parallel.

Although the original Nutcracker production cast students in the lead roles of Clara and the Nutcracker Prince (a sticking point for many critics at the time), the ballet nonetheless required a way to showcase the talents of a leading ballerina.

And so, the Sugar Plum Fairy, the embodiment of a sugary sweet and all that is delectable in general, was born.

The First Sugar Plum Fairy Schemes For More Stage-Time

Antonietta Dell’Era, an Italian dancer guesting from a company in Berlin, debuted as the first Sugar Plum Fairy at the Marinsky Theater in St. Petersburg in December of 1892. Strange though it may seem now, The Nutcracker initially received very mixed reviews. Dell’Era’s technique and pointework were lauded by many critics (2), but she received an infamously harsh review from one writer who described her as “ponderous”, “unbeautiful”, and “ungraceful” (3). However, according to author Jennifer Fisher, his opinion may well have reflected his distaste for non-Russian dancers more than anything (4). Apparently, the audience gave Dell’Era five curtain calls (5).

Dell’Era, however, seemed to have wished that the Sugar Plum Fairy had more stage time. So, in a later performance of The Nutcracker, she added an extra dance for herself– a gavotte by Hungarian composer Alphonse Czibulka (6). Though a cringe-worthy move from a modern perspective, supplementing a ballet’s score was certainly not unheard at the time. It’s also worth remembering that Tchaikovsky’s score for The Nutcracker was not yet considered a masterwork and initially received mixed reviews as well. Still, as dance critic Jack Anderson aptly wrote, “Surely Czibulka’s gavotte did not harmonize with Tchaikovsky, however effective it may have been as a showpiece for dell’era” (7). Again though, in Dell’Era’s defense, the Sugar Plum Fairy does indeed have significantly less stage time than leading ladies in other story ballets, though this would eventually prove a negligible issue.

Photo by Rachel Hellwig.

Is Plum’s Cavalier A Flirt?

Though the title is rarely used today, in earlier productions of The Nutcracker, the Sugar Plum Fairy’s dance partner bore the name of Prince Koklush or Coqueluche, which, oddly enough, translates to “whooping cough”. Yes, you read that correctly! But, it most likely was not referring to an illness. George Balanchine suggested that it might “represent a lozenge or cough drop” (8). Jack Anderson says that the term can also have the connotation of a flirt or a dandy (9). At any rate, perhaps it’s best that the character just goes by Cavalier or Prince now!

The original Prince Coqueluche was performed by Russian dancer Pavel Gerdt. Though in his late forties and no doubt past his technical prime, he was an acclaimed star with a long history on stage. Interestingly, for the history of Tchaikovsky’s ballets, Gerdt was also the original Prince Désiré in The Sleeping Beauty (1890) and Prince Siegfried in the successful 1895 revival of Swan Lake.

Photo by Gabriel Saldana. Licensed under CC Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic. [Changes to photo: filters added]

A Hidden Homage

The Sugar Plum Fairy’s solo or variation is perhaps the most recognizable selection from The Nutcracker’s score. The use of the celesta, a new instrument in Tchaikovsky’s time, plays a significant role in the music’s otherworldly sound. John Snelson, in an article for the Royal Opera House’s website, writes,

“Petipa asked here for music that sounded ‘as if drops of water were shooting out of fountains’, and Tchaikovsky matched this description superbly to the sounds of the celesta […]”

In contrast, the pas de deux of the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Cavalier has a distinct solemnity, if not somberness or ache, underneath its soaring grandness. This music may also be intended to be otherworldly, but perhaps in a different sense than the Sugar Plum Fairy’s variation.

Tragedy struck Tchaikovsky while he was composing The Nutcracker. His sister Sasha died. The event impacted both his work and his perspective of it. A 2011 article from The Guardian by Gavin Plumley explains, “After Sasha’s death, the composer embraced the ballet. In Clara, he found a parallel for his sister. Memories of their childhood and the last Christmas they spent together, in 1890, fueled the music. The whole ballet was transformed by his change in attitude, with Tchaikovsky imagining himself as the magician Drosselmeyer.” How does this color the pas de deux? Jennifer Fisher writes, “Musicologist John Roland Wiley has suggested that Tchaikovsky actually left a coded message in the rhythm of the adagio’s principal melody, a descending scale of notes that is repeated “with prayer-like insistence.” Because the phrase bears a close rhythmical resemblance to a line in the Russian Orthodox funeral service (which translates as “As with the saints give rest”), Wiley believes it might have been Tchaikovsky’s hidden homage to his sister” (10).

!["Kansas City Ballet, KCB Company Dancer Tempe Ostergren Photography by Rosalie O'Connor" by KCBalletMedia. Licensed under CC Attribution 2.0 Generic. [Changes to photo: cropped, filters, and background added]](https://www.danceadvantage.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/KCBalletMedia-Sugar-Plum-Edit-3.png)

“Kansas City Ballet, KCB Company Dancer Tempe Ostergren Photography by Rosalie O’Connor” by KCBalletMedia. Licensed under CC Attribution 2.0 Generic. [Changes to photo: cropped, filters, and background added]

Sugar Plum’s Enduring Appeal

The widespread success of The Nutcracker in North America during the twentieth century, propelled in large part by the triumph of George Balanchine’s version, afforded the Sugar Plum Fairy an unprecedented rise to power, especially after ballet companies coupled The Nutcracker to the holiday season. Dance critic Judith Mackrell attributes this acquired aura of the “promise of Christmas”, along with Tchaikovsky’s marvelous music, to the enduring appeal of the character, despite her lack of stage time and technical demands when compared to principal female roles in other ballets.

Furthermore, because of The Nutcracker’s family-friendly, holiday tradition status, it’s often the first ballet that children see and perform in. Naturally, the Sugar Plum Fairy is the first role that many young ballerinas-to-be aspire to. She is not only a symbol of seasonal splendor and hope, but the symbol of childhood dreams, and, for some dancers, the first childhood dream-come-true in their ballet lives.

Photo by Rachel Hellwig

~Endnotes~

(1) E. T. A. Hoffmann, Alexandre Dumas, Nutcracker and Mouse King and the Tale of the Nutcracker, Translated by Joachim Neugroschel, Introduction by Jack Zipes, (United States of America: Penguin Classics, 2007), p. 145

(2) Jennifer Fisher, “Nutcracker” Nation, (New Haven and London: Yale University, 2003), p. 15

(3) Roland John Wiley, Tchaikovsky’s ballets: Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, Nutcracker, (Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 144

(4) Jennifer Fisher, “Nutcracker” Nation, (New Haven and London: Yale University, 2003), p. 15

(5) Ibid

(6) Jack Anderson, The Nutcracker Ballet, (Hong Kong: Mayflower Books, 1979), p. 53

(7) Ibid

(8) Solomon Volkov, Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky: Interviews with George Balanchine, Translated by Antonina W. Bouis, (Anchor Books, Doubleday, 1992 Anchor Books Edition, originally published in hardcover by Simon and Schuster, 1985) p. 153

(9) Jack Anderson, The Nutcracker Ballet, (Hong Kong: Mayflower Books, 1979), p. 50-51

(10) Jennifer Fisher, “Nutcracker” Nation, (New Haven and London: Yale University, 2003), p. 10

Rachel Hellwig is a dance writer/editor/blogger from Birmingham, Alabama. She enjoys taking ballet classes, reading about dance, and attending live performances of ballet and classical music. She blogs at Clara’s Coffee Break. Read Rachel’s posts.