On the first page of her memoir, dancer Lee Wilson voices an important nugget of truth in a single line:

On the first page of her memoir, dancer Lee Wilson voices an important nugget of truth in a single line:

“In the 1950s and 1960s, many people thought of dance as a pastime for pretty young girls before they settled down and got married.” (p.1)

Women in the Fifties and Sixties had far fewer career choices than they do now and far fewer than men in the same time period. Wilson reminds us that, although women, such as Lucia Chase and Agnes de Mille, and gay men, such as Antony Tudor and Jerome Robbins, were the dance company directors and choreographers, it was a white straight man who was acknowledged as transforming ballet for America: George Balanchine. (p. 97)

Throughout the memoir, Wilson – who spent the bulk of her ballet career in Europe – is an interested observer in the American dance scene. She places it in historical context for us and gently reminds us that the world is a far larger place than most Americans imagine, such as she discovered when President Kennedy was shot while she was in France. Expecting to find a special edition of the local paper, she was told, “Of course not…this isn’t America.”(p.171)

A native of Delaware, Wilson grew up with three younger brothers in a traditional home. Her father worked and her mother raised the children. But from a young age, Wilson knew she wanted more than that. During a visit to her father’s office one day, where she saw him being waited on by his secretary and lounging in air-conditioned comfort while Wilson’s mother worked her fingers to the bone at home, she realized, “I wanted to be a person who worked.” (p. 5)

From the outset, she was determined.

She was a small woman, with a self-described non-ballerina body, and didn’t have a wealthy family supporting her. She was up against tough odds to become a professional dancer but she did it through hard work and sheer willpower. After lessons in Delaware and later Philadelphia, she auditioned for Julliard but did not get in. Her mother brought her to the Professional Children’s School in New York City so she could graduate early and get moving on her professional career as a dancer. She also took classes at Ballet Theatre School (which would funnel students into American Ballet Theatre) and thrived.

But when it came time to graduate and audition for companies, the market in New York City was either unstable (ABT) or unappealing (NYCB). This line from Wilson sums up her opinion at the time quite succinctly:

“The more I thought about…the New York City Ballet, the less I could see myself in an environment apparently dominated by one man.” (p.65)

And so, when the opportunity arose to move to Europe (her father was offered a job in Geneva, Switzerland), she jumped for it and thus began her career in the international world of ballet.

Throughout the book, Wilson brings the reader back to the financial practicality of being a dancer. While Wilson’s mother might have been supportive of her career in her own way, Wilson’s father made all the money – and all the decisions about what to do with it. With each step she took, she needed to prove to him that she was deserving of an allowance to buy pointe shoes and take ballet classes. As an underage dancer, her goal was always to become a working professional, with a steady contract and income. Naively she believed that she could live on a dancer’s salary and would be hired full-time with a company when she came of age. In each city and with each job she worked more and made more contacts, but she was only eking out a living along the way. Several times her mother simply said no, that her father would not pay for something and that it was up to Lee herself – at the young age of sixteen or seventeen – to figure out a way to pay for it. That’s a lot of responsibility to place on a child’s shoulders, especially one living in another country.

Despite the financial limitations, the careful parceling out of funds to pay for decent meals and proper housing, Wilson enjoyed a career highlighted by dancing with Rosella Hightower and in front of European royalty. She saw ballets and operas and took class beside Rudolf Nureyev. After returning to the United States, she danced on Broadway in “A Chorus Line” and “Oklahoma” among many others. She closes her memoir with this line:

“At a time when society clipped the wings of women and pushed them into subservient positions, dance allowed women to soar.”

Lee Wilson graciously agreed to answer some questions I had after reading her memoir.

Leigh Purtill (LP): Did your independence have any impact on your mother’s life?

Lee Wilson (LW): I don’t know if my choices had any impact on Mom, but her choices had a great impact on me. When Mom was twenty-one, she spoke five languages fluently. During World War II, she was an officer in U.S. Army Intelligence based in Washington, D. C., where her job involved breaking codes. But at the end of the war, women were pushed out of the workplace, and Mom, like most other women, got married and became a housewife. She homeschooled my brothers and me and washed out diapers in the toilet. She was financially dependent on Dad and a second-class citizen in society. At the ballet, women could be the stars. Men and women were equally respected and equally paid, and I wanted to be part of that magical world.

LP: How do you feel ballet has changed for women in the decades beyond those covered in your memoir?

LW: In mainstream society, women have more power than they had in the 1960s. In ballet, they have less. The most powerful position in a ballet company is the artistic director because she chooses the repertoire and hires the choreographers and the dancers. In the 1960s, Lucia Chase ran Ballet Theatre; Dame Alicia Markova was director of the Metropolitan Opera Ballet, and Rebekah Harkness founded the Harkness Ballet. Today the ratio of female to male artistic directors is much lower than in the 1960s, and the vast majority of choreographers are still male.

LP: Do you see new challenges for ballet to remain relevant? Do you see the differences between Europe and the US as clearly as they were when you were dancing?

LW: Ballet will remain relevant as long as choreographers tell stories that audiences want to see. According to a 2011 Dance/USA survey, women buy 77% of ballet tickets, so successful ballets must appeal to women. Since 35% of female ticket buyers have children in the home, some new ballets should appeal to families. This doesn’t mean that ballets can’t have sex and violence. Romeo and Juliet has both, but it also has a sympathetic, three-dimensional female lead, a fast-moving plot, and an inspiring, cathartic ending as the warring families reconcile. The most popular and enduring ballets are story ballets, so as long as choreographers come up with compelling stories and tell them musically and dramatically, ballet will be relevant. Dancers in major companies can perform dazzling pirouettes, thrilling leaps, and jaw-dropping lifts. The best of the best are extraordinary actors as well, so the execution of the choreography is in excellent hands.

There are still big differences between the U.S. and Europe. People in the U. S. glorify individual achievement, fame, and money. In Europe, the focus is on things that benefit the community: infrastructure, health, education, and the arts. The difference in focus affects everything from how and what people eat to the cost of ballet tickets or a college education to the number of homicides in schools, churches, and movie theatres.

LP: Your memoir ends with a note that you transitioned to a career in Hollywood. Can you expand a bit on that?

LW: My last Broadway show was “Meet Me in St. Louis.” After it closed, I was given the opportunity to write a holiday special, “The Elf Who Saved Christmas.” When it aired, the show received excellent ratings and reviews, and USA Network requested a sequel, “The Elf and the Magic Key.” Shortly after that, I wrote a TV movie, “The Miracle of the Cards,” which is based on a true story. It took forever to get the life story rights, but I produced the film in 2001, and it won the 2002 Epiphany Prize.

Lee Wilson made her debut as a classical ballet dancer at the age of sixteen in a command performance for Prince Rainier and Princess Grace in Monte Carlo. She danced for gun-toting revolutionaries in Algeria, American aristocrats at the Metropolitan Opera, and a galaxy of stars on Broadway. She worked with many of the great dancers and choreographers of the late 20th century, including Nureyev, Bruhn, Markova, Hightower, Ailey, and Bennett. She is an award-winning actress/writer/producer.

She currently lives in Los Angeles and can be reached through her website: www.leewilsonpro.com.

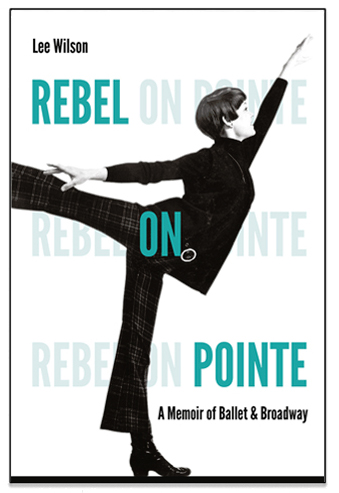

Her memoir, Rebel On Pointe can also be purchased through Amazon.

Leigh Purtill is a ballet instructor and choreographer in Los Angeles where she lives with her husband and charming poodle. She received her master’s degree in Film Production from Boston University and her bachelor’s in Anthropology and Dance from Mount Holyoke College. She is the author of four young adult novels from Penguin and HarperCollins. She is the artistic director of the Leigh Purtill Ballet Company, a nonprofit amateur ballet company for adults and she teaches ballet and jazz to adults both in person and online, Leigh Purtill Ballet. Read Leigh’s posts.