When preparing for ballet exams dancers often hear the words ‘expression’, ‘communication’ and ‘performance’.

Yet, without a character from which to draw inspiration, how exactly are you supposed to be “more expressive”?

This article explains how to tap into your inner performer and breathe life into your work.

Performance

The word ‘perform’ is often misinterpreted as meaning ‘big toothy grins and jazz hands’, or ‘adding more personality’, yet the true art of performance is more substantial, a more involved process; something that is gradually mastered over the duration of a dancer’s full career.

In its simplest of breakdowns, I think of performance as incorporating:

• Charisma

• Stage Presence

• Artistic Sensitivity

Together meaning the dancer holds an underlying sense of calm confidence, has a certain irresistible attractiveness, or commands attention, and that they respond sensitively to the material performed.

“Dancing is an art, and as in all arts, quality and technique are inextricable.” – Maria Fay

Charisma & Stage Presence

While two slightly different things, you can learn to develop both simultaneously using similar imagery techniques. Here are a few to experiment with:

- Imagine bright warm sunbeams are radiating out of you from your centre, surrounding you with light.

- You are an authoritative aristocrat – you are expensive, powerful and valuable. You are wearing fine clothes, have jewels across your chest, and a crown upon your head.

- You are standing on top of a huge mountain with the sweet-smelling breeze blowing past your neck and ears, looking way out into the distance.

- Imagine your body is sparkling, like water reflecting sunlight (Eric Franklin).

- Think back to a time when you felt extremely happy or proud of an achievement. Try to recall that sensation and surround yourself in it. Let those positive emotions emanate from you like an aura.

Ultimately you want to embody energy, passion and confidence, but balance that with a sense of calm and self-assuredness. You want to feel quite powerful, but very generous of spirit.

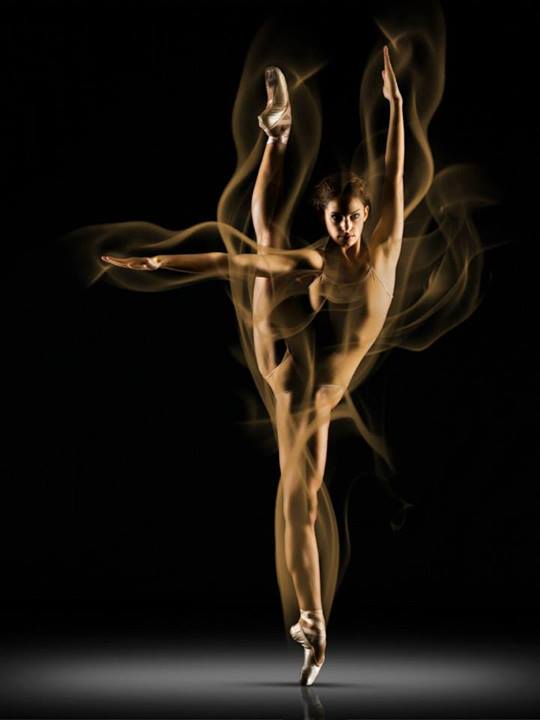

There needs to be a sense of presence in your movements: to be in your own body and in the moment; your movements conveying thoughtfulness, care and a mindfulness of classical purity, without ever becoming robotic.

You need to project a slight sense of abandonment and spontaneity as if you are dancing a piece for the first time; as if the music is being channeled though you and you are compelled to dance.

You want to have a strong sense of ‘self’ – feeling centered, and with a heightened awareness of the space you occupy, and the patterns you make in space. You need to feel the subtle articulations through your joints, and the arcs and curves you make in the air.

“Heightened awareness of the space you occupy, and the patterns you make in space.”

To further help illustrate these concepts, have a look at the following two videos:

● Guillaume Côté ‘Lost in Motion’:- This fantastic piece of choreography and cinematography perfectly encapsulates the concepts of both a heightened awareness of self, and the shapes and patterns you carve through of space.

● Shoko Nakamura’s Chacott/Freed Photo Shoot:– Watch how Shoko can strikingly portray mystique, cheekiness, flirtatiousness or the ethereal through the use of her head/eyeline. Also note the openness across her chest, the air underneath her chin, and how she engages her back muscles to make her arms more expressive.

“If the artist believes in what he is doing the expression of the face changes instinctively.” – Joan Lawson

Artistic Sensitivity

With syllabus work, it can initially be very difficult to identify with the set exercises and bring them to life. Four things to consider are:

1. The Rules and Principals Underpinning Classical Ballet

You need to become fluent in the rules of ballet, for there are many detailed conventions for almost every aspect of classical technique; from the placement of the fingertips to the subtle skill of flexing the elbows just the right amount for your arms to ‘breathe’. While this will be a long process, putting in the detail as you are studying will ultimately free you as a performer.

“Master technique and then forget about it and be natural.” – Anna Pavlova

2. The Music

Musicality is not only about responding to tempi (speed), but also mood and dynamics. What emotion does it convey? Does it sound like a happy exercise, or is it more somber or reflective? Is it energetic, or even furious? Remember: Don’t just count it, translate it.

“Dance is music made visible.” – George Balanchine

3. The Choreography/Setting

Very often there are subtle nuances of timing, or emphasis/accents placed on certain movements. Making sure you get the timing and the detail right will help give the work life, as it is those small differences that make ‘these’ tendus different to ‘those’ tendus.

4. Individual Interpretation

You want to have ownership of the work. To know it well enough that it becomes part of you, and you can add your own subtle individual interpretation. However neatly you might need to blend into your own corps de ballet (or class), your dancing should still always have your unique ‘stamp’ on it.

Considering artistic sensitivity, watch ex-Royal Ballet principal Lesley Collier discussing the importance of “expensive perfume” at 11:14…

Royal Ballet in rehearsal: The Nutcracker

Expression

Expression is about conveying thought or feeling to your audience. Without a character, this is easiest by being inspired by the music: first embodying, and then projecting the mood it evokes.

For example, if the grand battement exercise has a Spanish flair to the music, you want to capture that essence and reflect it in your movements; perhaps adding a slight flourish of the wrist when taking the arms to 5th in a final relevé, or adding a little more épaulement.

Expanding upon the ‘Spanish flair’ example, you could even take things one step further and imagine being Kitri in ‘Don Quixote’ and see how that changes your work. In this way, you can actually flip the whole equation around and derive character from the music which can further inform your artistic sensitivity and individual interpretation.

Watch how Royal Ballet Principal Zenaida Yanowsky as Prayer in ‘Coppélia’ beautifully conveys awe and hope, and contrasting mellow humbleness, using facial expression, eyeline and subtle movement dynamics; all the while responding to the music.

Royal Ballet - Coppelia pt. 10

Remember, pliés are often calm and reflective, battement tendus are sometimes cheeky, grand battements are often bold, and an adage can be a long walk on the top of a mountain… There is always something to work with.

Communication

‘Communication’ can be separated into two main components:

- Projection

- Connection

Projection

As classical ballet is a theatre art, it is important to learn to how to dance as if you always have a full auditorium of people watching you:

Expand But Don’t Exaggerate:- You must expand and enlarge your expressions and gestures to accommodate the distance between you and your viewers, but your delivery should never become so exaggerated that it becomes a parody, or ‘ballet pastiche’. You want to have truth in your movements.

Keep Your Energy Levels High:- It takes a lot out of a performer to maintain high-enough energy levels to keep projecting out to their audience. Building emotional and cognitive (intellectual) stamina takes practice – another reason why not to leave it to exam day to think about ‘artistry’!

Don’t Dance From The Waist Down:- Don’t exclusively focus on ‘learning the legs’ and think you can ‘add the arms later’, or fall into the trap of believing you can ‘layer on’ facial expression at the very last minute. Get used to dancing as a whole. The famous ballerina Natalia Makarova was a huge advocate of this practice.

“To dance is to be out of yourself. Larger, more beautiful, more powerful.” – Agnes De Mille

Connection

In order to communicate you need to connect with your audience – whether your spectators are real, imagined, or a single examiner:

Look To ‘The Gods’:- The highest seats in a theatre auditorium are often called ‘the Gods’. You want to dance for those guys. Project out and upwards.

Imagine a Conversation:- Pretend you are in the presence of a friend, and feel at ease with them. Imagine you are having a conversation with them; continually responding to the audience’s questions and requests. Share yourself, and the choreography, with them. [Adapted from Jeanette Stoner / Eric Franklin]

Give The Gift Of Yourself:- Consider the idea that all of your classes over the years have been preparation for this performance. Give yourself to your audience. Don’t hold anything back.

Above all: Communicate with them. Reach out to them. Connect with them – Keep life in your movements, and light in your eyes.

“You may have all the technique in the world, but only the true performer can touch an audience.” – Eric Franklin

Tips & Troubleshooting

• Make sure you know the choreography 100% ASAP and feel confident with it so you can devote your energy and focus to performance and expression.

• Take time out to really listen to the music: immerse yourself in it. Get a copy and listen to it outside of class (in a quiet room with no distractions is best). Then, when you’re dancing, you can more easily let your emotions radiate out through your movements and facial expression. Make it real.

• Don’t be afraid to use your imagination. Don’t be afraid to feel vulnerable. Don’t be afraid to put emotions into your work.

Above all: Don’t Fake It, Feel It.

Here is a lovely video of Zoia Miller performing as part of the Présentation des eleves de l’opéra (1999), beautifully demonstrating that even barre work can be dancing.

Zoia miller, Présentation des eleves de l'opéra, 1999 ( elle avait 10 ans)

References:

▪ Franklin, E. (1996) Dance Imagery for Technique and Performance. Human Kinetics Publishers.

▪ Fay, M. (1992) Not Training, but Teaching. Dance Gazette, Vol. 210, pp.32-33.

▪ Lawson, J. (1957) Mime: The Theory & Practice of Expressive Gesture. New York: Dance Horizons.

For more performance tips, check out Nichelle’s 7 Secrets of Super Performers.

What are the notes you’ve received most often regarding your performance skills?

Are there any tips you’d add?

Angeline Lucas is a freelance dance writer, teacher and lecturer based in England. She has been awarded Registered Teacher Status with the Royal Academy of Dance (RAD) and is an Approved Teacher of the Council for Dance Education & Training (CDET). Angeline trained at Northern Ballet School (NBS) and holds a Certificate of Higher Education in Dance Education, validated by RAD and the University of Surrey. Previous roles have included working as head of department, outreach coordinator and curriculum manager, and she also has experience in dance research and arts administration. Angeline has taught and lectured at various private dance studios, schools, colleges and on community programmes, and is considered to be a dedicated, experienced and enthusiastic teacher. Angeline’s greatest passion is classical ballet, and is devoted to the advancement of the art form, the promotion of accessible high-standard dance education, and facilitating the achievement of her students.