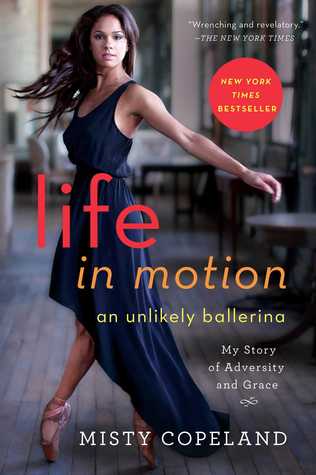

In Misty Copeland’s new memoir, “Life in Motion: An Unlikely Ballerina,” she writes about “white ballets” such as La Bayadere and Giselle, and in particular, the “white act” of Swan Lake. Professional dancers understand the importance of synchronicity of movement in ballet; they know that very tall ballerinas are hard to partner, that dancers with short legs do not have the same arabesque as dancers with long legs. But skin color? Must that be the same as well?

Not only did Copeland paint her skin a different color in order to play roles in Giselle and Sylvia, but it was also a joke among her fellow dancers:”You’re the only black girl, Misty, but you’re always playing an animal that has to be white.” She laughed along – simply happy to be a member of the world famous American Ballet Theater – until it was too much: “I began to think that it wasn’t so funny.”

1957? 1977? No, this was 2007.

Misty Copeland’s journey in ballet began when she was thirteen, a very late start for a dancer, especially one destined to become a star. Many fans know her first dance class was at a Boys and Girls Club in San Pedro, California. Her body was perfectly designed for ballet but she didn’t know it until she met Cindy Bradley, a ballet instructor who recognized her potential. Copeland and her family moved a great deal, and there wasn’t much money for luxuries like ballet lessons and expensive pointe shoes, so when Bradley offered to take young Misty into her home in order to help pave the way for a successful dance career, Copeland’s mother felt she had no choice. Copeland writes, simply and heartbreakingly, of the moment her mother agreed to Bradley’s request to let Misty live with her:

“And she let me go.”

Two years later, after Copeland had begun drawing attention in the dance world by winning the prestigious Los Angeles Music Center’s Spotlight Award and performing in ballets like Debbie Allen’s “The Chocolate Nutcracker,” Copeland’s mother and Cindy Bradley would be in a custody battle over Misty as she tried to emancipate herself. That battle would be waged very publicly, including an awkward appearance on the talk show Leeza. Shy, intense Misty was mortified by the negative attention of the media. All she wanted to do was dance.

A dream comes true.

Since she’d initially fallen in love with ballet, American Ballet Theater had been Copeland’s dream company. Although she’d been accepted into the summer programs of every major company in the country (except New York City Ballet, a rejection she says was based on her skin color) and had attended San Francisco Ballet’s program, it was ABT’s program she wanted most. When ABT offered her a full scholarship to their summer intensive, off she flew to New York.

But leaving the relative cocoon of San Pedro meant exposing herself to the harsh judgments of the professional ballet world, a world that has long been very homogeneous, some would say, very white. While Copeland had experienced racism back home, she was primarily surrounded by a supportive family, but in New York, she found subtle and not-so-subtle hints that she was not welcome. That judgment became more pronounced when she suddenly developed from an adolescent into a young woman, complete with curves in all the wrong places for ballet. Hers was the body of an African-American woman and at first, she abhorred it. She was embarrassed and disapproving of her own body; thankfully she did not develop an eating disorder, but despite her efforts, the shape of her body did not change. And ABT – from the costumers to management – asked her to lose weight, to get her “line” back, the one for which she’d been hired.

“…my curves are part of who I am as a dancer, not something I need to lose to become one.”

Eventually, she came to accept her body: “I had breasts, and muscles, but yes, I was still a ballerina.” And her acceptance of herself led to ABT’s acceptance of her as well. They stopped asking her to change who she was and began to celebrate her difference, promoting her to soloist in 2007.

Misty Copeland is only the third African-American female soloist with American Ballet Theater and the first in nearly twenty years.

Discuss “Life in Motion” live on Dance Advantage today, December 19 at 3:30 EST. It is a perfect opportunity to talk about some of the adverse situations Misty Copeland has experienced as well as racism and diversity in general in the world of ballet and dance.

Some topics for our discussion:

- Racial diversity in professional ballet as well as local studios

- Economic discrimination in ballet: pointe shoes v. groceries

- Teachers: external challenges we face with students

- Students: dealing with and overcoming family obstacles

- Shy Misty and the need to perform

- Misty leaves home – how far should parents go to encourage their children?

- Curves and growth; how do we handle body changes in young dancers?

Tell us what you think of Life in Motion.

Leigh Purtill is a ballet instructor and choreographer in Los Angeles where she lives with her husband and charming poodle. She received her master’s degree in Film Production from Boston University and her bachelor’s in Anthropology and Dance from Mount Holyoke College. She is the author of four young adult novels from Penguin and HarperCollins. She is the artistic director of the Leigh Purtill Ballet Company, a nonprofit amateur ballet company for adults and she teaches ballet and jazz to adults both in person and online, Leigh Purtill Ballet. Read Leigh’s posts.