Having addressed the Cervical and Thoracic spines in previous installments, we now turn our attention to the lower three sections of the vertebral column.

Structure and Function:

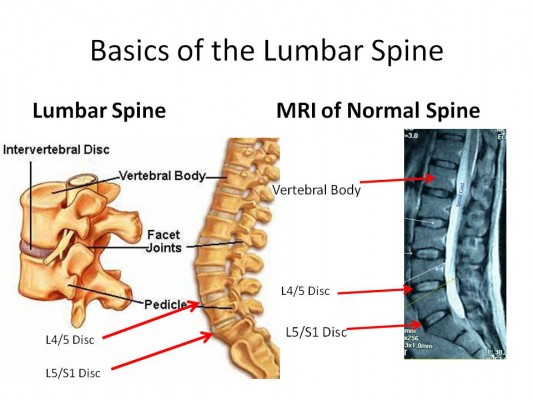

The five bones of the Lumbar Spine generally follow the same rules as the other vertebrae. On occasion, some individuals have four or six lumbar vertebrae, but five is most common. Located in the lower portion of your back, L1-L5 are the largest of all the vertebrae, and form a concave curve. The bodies tend to be larger than cervical or thoracic vertebrae, and the spinous and transverse processes are smaller and thicker.

The five bones of the Lumbar Spine generally follow the same rules as the other vertebrae. On occasion, some individuals have four or six lumbar vertebrae, but five is most common. Located in the lower portion of your back, L1-L5 are the largest of all the vertebrae, and form a concave curve. The bodies tend to be larger than cervical or thoracic vertebrae, and the spinous and transverse processes are smaller and thicker.

All of these minor variations serve the primary function of the spine, which is to carry the weight of the body and transfer it to the pelvis. Logically, a structure that has a larger base of support is stronger, and the vertebral column is no exception. What makes the spine special is that it is composed of curves. As dancers, we typically work to eliminate these curves through continually “straightening” the spine. It’s true that an elongated spine is important; injury is most likely to occur at the sharpest point of the curve, so lengthening the spine reduces the chance of injury. However, a dancer who appears to have a straight spine, while she may have diminished the curves to some extent, still maintains a degree of curvature. Unlike a rigid, straight structure, the curves of the spine, in combination with the intervertebral discs, absorb shock and prevent wear and tear on the vertebrae.

Intervertebral Discs:

Between each of the vertebrae is an intervertebral disc. This fibrous, cartilage-ish cushion provides space between the bones, allowing for movement of the spine. To better understand this concept, take two toy blocks and put them together. While they can move as a unit, neither block can move independently because of their rigid structure. Now separate the same blocks by about a half-inch and notice that you have space to move each block forward and back, side to side, independent of the other.

In addition to facilitation of movement, intervertebral discs also provide the shock absorption mentioned above, and bear the weight of the body. The posterior and anterior longitudinal ligaments, in addition to the supraspinous ligament, act as a brake to flexion and extension, protecting you from injury to the disc. However, if enough pressure is placed on the spine on a consistent basis, the tough membrane of the disc may become torn. This is referred to as a bulging disc. The disc places pressure on the spinal cord, causing back pain that can be quite severe. If the disc starts pushing through the torn membrane it has become herniated. 80% of all herniated discs occur in the lumbar spine, and symptoms include extreme pain in the injured area, numbness and muscle weakness in the pelvis and legs, and occasionally partial (usually reversible) paralysis.

Herniated discs can, and many times do, heal on their own, provided you take the proper precautions of rest, ice, etc. However, this is a very serious injury that, in some cases, requires surgical intervention. Be sure to seek medical advice if you suspect any sort of disc injury.

The Caboose…

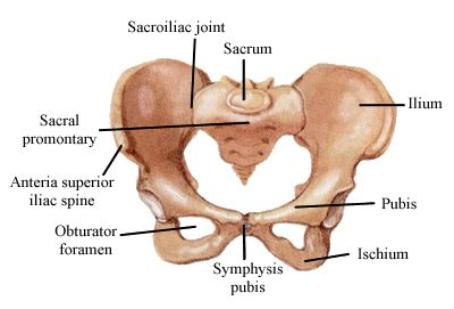

At the end of the vertebrae column are two unique structures called the sacrum and coccyx. Though they bear little resemblance to the rest of the spine, both structures are composed of vertebrae that are separate at birth and gradually become fused as the child develops. The sacrum rests between the two pelvic bones and is shaped slightly differently in men and women (as is the pelvis, due to the woman’s role as childbearer).

At the end of the vertebrae column are two unique structures called the sacrum and coccyx. Though they bear little resemblance to the rest of the spine, both structures are composed of vertebrae that are separate at birth and gradually become fused as the child develops. The sacrum rests between the two pelvic bones and is shaped slightly differently in men and women (as is the pelvis, due to the woman’s role as childbearer).

The coccyx is a largely ignored remnant of human evolution, and commonly referred to as the tailbone. However, the coccyx is the attachment site of the muscles of the pelvic floor, and many ligaments.

Consequences of imperfect posture:

Since the abolition of waist coats and corsets, the posture of the general population has been getting gradually worse.

If you sit up tall on the floor with your legs crossed, and rock gently back and forth, you’ll feel the bony prominence of each pelvic bone. These are called the ischial tuberosities, or commonly called the “sitz bones”. Though called bones, they are actually little knobs that are part of the pelvis – one of the largest bones in the body. Now tuck your pelvis and rock slightly backward (still sitting). You may feel slight discomfort here, especially if you have a very low body fat composition. You are now placing the majority of your weight on the coccyx – three of the tiniest bones in the body. Tailbone injuries are quite common in dancers and can be very tricky to diagnose and treat. Pain in the area can be associated with a sprain or strain (recall that this is the attachment site for many muscles and ligaments), dislocation, or fracture, due to an acute incident or chronic wear and tear. This amalgam of conditions is generally referred to as coccydynia. As if we didn’t need another reason to pull up…

Well, friends, here concludes my exhaustive analysis of the spine.

When I set out to write a brief exposé on the vertebral column and posture, it quickly became clear that it was not possible to do so with any sense of brevity. Just in case you missed anything, here a brief synopsis of what I think it’s important to know about the spine:

1. The architecture of the spine follows many of the same rules as other tall, thin structures. At the same time, it is totally unique in the way that it curves. As dancers, we continually attempt to minimize those curves in order to reduce the chance of injury. Not to mention it looks nice.

2. The spine is a system, not a thing. Each part is interdependent on the other parts. That’s why it’s important to use caution when correcting the placement of the spine. Be sure that by correcting one error you are not creating another.

3. There are more reasons to sit up straight than simply minding our mothers… chronic and excessive slouching can contribute to pathological conditions such as kyphosis and coccydynia. For members of the general population, dance is a wonderful way to strengthen and increase flexibility of the spine, and may help reduce the impact these conditions.

Next time on Art Intercepts:

Knees, please: common knee injuries and practical prevention

—

References:

Beers, M. H. (2003). The Merck Manual of Medical Information, Second Edition Pocket Books, 569-570.

Calais-Germain, B. (1993). Anatomy of Movement. Seattle: Eastland Press.

Dollinger, V., Obwegeser, A. A., Gabl, M., Lackner, P., Koller, M. & Galiano, K. (2008). Sporting activity following discectomy for lumbar disc herniation. Orthopedics 31, 756-764.

Grieg, V. (1994). Inside Ballet Technique: Separating Anatomical Fact from Fiction in the Ballet Class. Hightstown, NJ: Princeton Book Company.

Henry, L. (2008). A calf tear of suspicious origin: a case study. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science 12, 32.

Lauren Warnecke is a freelance writer and editor, focused on dance and cultural criticism in Chicago and across the Midwest. Lauren is the dance critic for the Chicago Tribune, editor of See Chicago Dance, and founder/editor of Art Intercepts, with bylines in Chicago Magazine, Milwaukee Magazine, St. Louis Magazine and Dance Media publications, among others. Holding degrees in dance and kinesiology, Lauren is an instructor of dance and exercise science at Loyola University Chicago. Read Lauren’s posts.