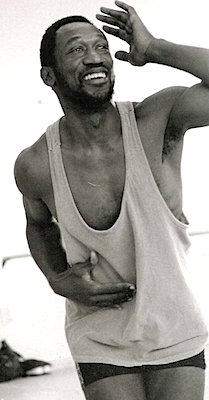

David Alonzo Jones has been a guest instructor for both Dance Masters of America and National Association of Dance Artists, and is a professor of Dance at the College of Marin. Today, he shares one of his favorite tools for helping his students learn combinations, routines, and choreography and why it’s become so.

I remember it like it was yesterday.

A group of guys and girls in a dorm complex at the the University of Oregon trying to learn some movements to music that some theater guy wanted to put together for a presentation.

A group of guys and girls in a dorm complex at the the University of Oregon trying to learn some movements to music that some theater guy wanted to put together for a presentation.

Even though at the time I had been a starter on the frosh football team, the opportunity caught my interest and so, there I was, with a number of other closet-dance lovers, trying to learn what I later would get to know as choreography.

I remember, to this day, how frustrating that experience was.

The movements seemed easy enough, I could certainly hear the music and recognize the counts, but there was something about putting the movements together and remembering them that made things difficult and frustrating. And so was my introduction to sight-reading – the backbone of the dance performance experience.

Although very little is said about this skill, it is a fundamental, and I do mean fundamental, element of the dance experience, both in class, and for the development of performance pieces.

Sight-reading dance

I call sight-reading in dance the ability to repeat movements that have just been demonstrated with as much detail and accuracy as possible. It is a cousin to quickly learning a script in drama or reading sheet music. This includes which movements occur when in association with a piece of music, so this means not only learning movements in sequence, but in rhythmical order and/or syncopation. Sounds difficult, and it is.

The dance class is where sight-reading abilities are developed. African, Ballet, Modern, Tap, Jazz, and Hip Hop all employ this element at some point in the class. To some extent, dance exercise classes place emphasis on sight-reading, but since these classes focus on giving the students a ‘workout’, the movement vocabulary is relatively limited, which in turn abbreviates the movement content and tends to make the choreography somewhat repetitious.

Years of observation

My teaching experience has led me to believe that woman are naturally better at sight-reading than men. Over the years, the men in my classes have always fallen behind women in this ability. Perhaps future research will reveal why this is the case. My own theory is that women are more open to cooperative/social activities than men, so when they are placed in a group activity with a common cooperative goal, they readily adapt and learn.

I have noticed that, oddly, some of the seemingly most capable academically and/or intellectually, seem to have the most difficult time with sight-reading. If one accepts the idea of the existence of left brained and right brained people, we could say that left brained people, although great with mastering language skills, have a more difficult time with right brain skills like spatial orientation, which sight-reading requires.

Generally, the longer you take classes, the easier it becomes to read and remember movement, and so in that respect it is a skill that you learn by doing. Certainly, it is a skill that makes dance student recitals possible, and generally accompanies the dancer as she/he improves her/his technical skill.

Years ago, if you had difficulties reading and remembering movement in dance classes, or when attempting to learn choreography, you were just up the creek, and without a paddle. You had to swallow the idea that the desired sequences of movement, or choreography that you were attempting to learn was simply beyond your ability to grasp.

The Breakthrough

That was then. Things have changed. I have been using video as a tool to help dancers for the past ten years, and I am here to tell you that it works, and works well.

I have videotaped movement sequences and combinations from class and made them available for my students, and I have seen a phenomenal amount of progress in the students’ ability to remember class choreography. Of course, students have to be motivated to watch the videos and practice them.

Videos work because it just takes ‘X’ number of repetitions of seeing and attempting to do a movement sequence or routine before it can be mastered. You can run a video 1100 times if you need to, to finally memorize a pattern.

You won’t get that many reps out of a teacher in a class.

Mastery Enhances Sight-reading Ability

In my beginning classes, I usually have a semester combination. The video allows dancers to see patterns enough times for their minds to log them and then commit them to memorized sequences. As a result, the students perform that combination better.

The more you study with any teacher, the more familiar you become with the movements that they use and how they choreograph, so essentially your ability to pick up movements should improve regardless. Nevertheless, I have students who have taken class from me several semesters who still seem to enjoy the benefits the video provides.

Once a relatively ‘meaty’ combination is mastered, classes usually do quite well with future ones. So evidently, the whole process is enhanced by gaining a sense of mastery of that first routine and the confidence that comes from it.

For beginning students, and/or students experiencing a new instructor, it’s critical that, at some point, you experience that sense of mastery. This leads to more success.

Do you regularly incorporate video into your teaching/learning process?

David Alonzo Jones holds an MA in dance from Mills College. He began his studies at the University of Oregon where he performed with the Ballet Company. In the Bay Area, his mentors were Gwen Lewis and Ed Mock. He has been influenced by such noted jazz specialists as Gus Giordano and Joe Tremaine. He has worked with the Village People, Taj Mahal, Luciano Pavarotti, and Harold Nicholas of the famed Nicholas Brothers. He also worked with the cast of the Las Vegas spectacular “Jubilee”, and performed with the San Francisco Opera’s productions of “Lost in the Stars” and “Aida”, which was televised live in Europe.

___________________________

There’s an app for that:

Dance Journal costs $1.99 in the Apple app store. You can log each class you take and note what you learn, even adding video or photos to make things easier to remember. You can sort your entries by date, category, or instructor. And, if you have a friend with the app, you can send them your entries so that they can look at them too.

Dance Advantage welcomes guest posts from other dance teachers, students, parents, professionals, or those knowledgeable in related fields. If you are interested in having your article published at Dance Advantage, please see the following info on submitting a guest post. Read posts from guest contributors.