Unfortunately, no matter how careful you are, sometimes injuries happen.

Parts one and two of my three month “Meet your feet” series generally focused on maintenance and preventative actions to take for your feet. In this final installment of the series, I’m taking a closer look at injuries and how to cope throughout the recovery process.

There are two main categories of injury: acute and chronic

There are two main categories of injury: acute and chronic

Acute injuries result from a trauma or single occurrence, for example, landing wrong from a jump or trips and falls. Acute injuries can be very serious, but are often more easily detected and diagnosed than chronic injuries.

Chronic injuries develop over time and are usually the result of improper technique or overuse. Treatment and recovery can be tricky, because a dancer with a chronic injury must evaluate and address the flaws in her training and technique that caused the injury while simultaneously focusing on healing. Because of this, chronic injuries are more likely to recur.

Examples of Acute Foot and Ankle Injuries:

- Ankle Sprain

- Dancer’s Fracture (Fifth metatarsal fracture)

Examples of Chronic Foot and Ankle Injuries:

Aside from acute and chronic, injuries can be further categorized by the type of tissue that has been injured. Generally speaking, we divide acute musculoskeletal injuries into three groups: sprains, strains, and fractures.

“Sprain” and “strain” are terms that are sometimes used interchangeably, and other times used casually to describe discomfort (i.e. “I strained my hip yesterday”). In reality, sprains and strains are entirely different injuries…

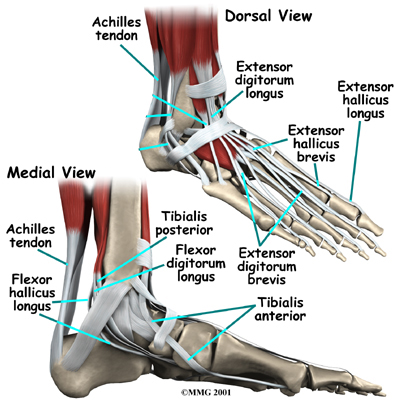

To understand the difference between strains and sprains, you should first understand the difference between tendons and ligaments. Tendons are made of elastic-y tissue and connect muscles to bones. Their main job is to transfer force produced by the muscle (actually by the brain… but you already know that) in order to move bones. An injury to a tendon is referred to as a strain.

Ligaments, on the other hand, are collagenous structures that run between bones providing protection and support over joints. A ligaments isn’t, by nature, very stretchy, so when it is stretched beyond a certain point it isn’t apt to recoil like a tendon will. Whether part of a traumatic injury or because of repeated use, a ligament stretched seriously beyond its limit (sprained) can no longer do its job of supporting the bones in a joint.

One of the most common injuries among dancers is ankle sprain, and because the stretching of ligaments around the ankle make the joint more unstable after injury, previous sprains are a big risk factor for becoming injured again (on the same side AND the opposite foot).

What to do in the event of a strain or sprain:

Strains are somewhat easier to deal with than sprains. The regenerative properties of muscle tissue render tendons able to heal relatively quickly on their own. Torn ligaments, on the other hand, are typically only fully repairable by surgery.

But I’m getting ahead of myself….

The first course of action in the event of an injury should always be “RICE”: Rest, ice, compression, and elevation. Compression is the tough one here; if you notice an extreme amount of swelling it’s not always advisable to wrap it because swelling is part of the natural healing process.

What IS advisable is seeing a doctor at your earliest convenience, and s/he can be the one to recommend whether or not it should be wrapped.

While it may be fairly simple and straight forward to treat a sprain or strain on your own, it’s always better to get a doctor’s opinion. It may not be evident whether or not the injury is related to tendons or ligaments, or if there is any additional injury. Ankle sprains, for example, are sometimes accompanied by a fifth metatarsal fracture (which, obviously, is not something you can ice and wrap and make all better).

As I eluded to, sprains can be a bit trickier because a completely torn ligament is really only repairable by surgery. The potential problems with reconstructive surgery are 1) the recovery time, and 2) the potential loss for full range of motion at whatever joint is injured. These are both of obvious concern to dancers, so if you find yourself facing surgery be sure your doctor explains all the risks and allows you to weigh your options clearly.

Moreover, and perhaps most importantly, part of the recovery process of any injury should include a heightened awareness of what caused it, and how to prevent future injury. That means checking in on technique, training conditions, environmental factors (such as floors, temperature, etc), and psychological barriers. Too often dancers don’t give enough time and attention to the recovery process because they fear being forgotten or replaced. As directors, teachers, administrators, and academics, we can change this culture to help reduce the number of dancers who end their careers permanently by dancing through injury unnecessarily.

How have you coped with injury in the past to prevent further setbacks?

Lauren Warnecke is a freelance writer and editor, focused on dance and cultural criticism in Chicago and across the Midwest. Lauren is the dance critic for the Chicago Tribune, editor of See Chicago Dance, and founder/editor of Art Intercepts, with bylines in Chicago Magazine, Milwaukee Magazine, St. Louis Magazine and Dance Media publications, among others. Holding degrees in dance and kinesiology, Lauren is an instructor of dance and exercise science at Loyola University Chicago. Read Lauren’s posts.