A Window into Your Students’ Knowledge and Expression

Over this past year, I have been a member of the Michigan Arts Education Instruction and Assessment project (MAEIA) funded by the State of Michigan’s Department of Education and the Michigan Assessment Consortium. We have been tasked with creating a blueprint for premiere arts education for the K-12 public education system as well as developing Assessment Specifications and are now moving on to the Assessment Item Development.

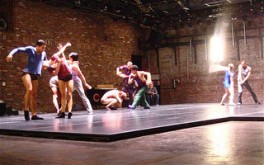

Through this work, we have been looking at three major strands through which we experience dance: Create, Perform, and Respond. For me, personally, there have been a lot of revelations within the process of the MAIEA project but perhaps none more than in the aspect of composition as a tool for really seeing students and the depth of what they know.

Traditionally, composition assignments relate to a “theme” or a narrative to be expressed through movement. We have loads of editing tools to develop our voice, our perspective, and our impact on the viewer. However, if only used in that narrow scope, the act of creating dances feels largely like an untapped resource of experience for students’ to mine their depth of knowledge and cultivate their breadth.

Creating to Demonstrate Technical Understanding

This marking period, we have been focusing on “specificity of movement”. This, in particular, has featured how the spine moves, the feet should roll through to extension and flexion, distinctions of weight shift, and carriage of the arms. We have examined each of these concepts from large over-views to detailed information about the anatomy of the body and technical imagery that helps us achieve these movement goals.

I have taught with these concepts present in each of our class segments: conditioning, a modified version of BrainDance, technical warm-up and theory, progressions, and movement studies.

And then I turn it over to the students. In groups, they “create” their own exercises with these principles in place. When it comes to choreographing movement studies, they are encouraged to “predict” more advanced versions of the material I have exposed them to and include those ideas within their work.

Fascinating questions arise and soon their “can we” inquiries leave the request for permission behind and move into “Can the body do this? How? Should we change the order?” The theoretical discussion becomes their own and primes introductions to various choreographers based on the questions they asked of the body, of dance, of an audience.

Creating to Express

Naturally, choreography is a window into where artists “are” in their lives at any given time. In fact, it can be hard for a choreographer to revisit “old” works because they aren’t in the same place in life as when they created it.

This is no different for middle school or high school students and it is a great way for them to measure their development. Pre- and post- tests are common in all subject areas but it can be actually meaningful and fun in dance composition.

Often, we revisit composition sketches developed earlier in the year by viewing the video created, asking what they would do differently now they have more experience and allowing the student artists to make changes. Sometimes, we get so wrapped up in editing current work with students that we don’t allow them the process that we as professionals tend to engage in- allowing the dust to settle before we revisit our work with new eyes.

Creating to Respond: Physical Note-taking and Priming Class Discussion

As an “elective” teacher, my class community includes a wide array of learners with varying academic needs, levels, and experiences. One of the most common phrases among students new to my class is, “why do we always have to write?”. The “we” in that statement is the student collective not just the “we” dancers.

Yes, students are always expected to write, yet, there are other ways to measure their understandings, responses, and evolving thoughts that don’t include pen and paper, just as demonstrating their notes about a dance they have viewed through movement excerpts and modifications to address the oral discussion to be shared within the class as I proposed in Measuring Success: Data-Driven Dance.

How are your students offering insight?

Further reading:

Careers in Dance: The Path from Dance Major to Choreographer

Heather Vaughan-Southard MFA, is a choreographer, dance educator, and performer based in Michigan. She currently directs the dance program at the Everett High School Visual and Performing Arts Magnet in Lansing. With the philosophy of teaching dance as a liberal art, Ms. Vaughan-Southard collaborates with numerous arts and education organizations throughout the state. She has danced professionally in Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, and New York and has performed works by Mia Michaels, Lar Lubovitch, Donald McKayle, Billy Siegenfeld, Alexandra Beller, Debra Levasseur-Lottman, and Bob Fosse. As a choreographer, her work has been credited by the Los Angeles Times for “creating heat.” She has recently choreographed for the dance programs at Michigan State University, Grand Valley State University, Lansing Community College and is the former dance professor at Albion College. She is a regular guest artist and blogger for Dance in the Annex, an innovative dance community in Grand Rapids. Heather received her MFA in Dance from the University of Michigan, BFA in Dance from Western Michigan University and K-12 certification in Dance from Wayne State University. Read Heather’s posts.