Thirty years ago, author Cherie Magnus and her son performed as supernumeraries (the “extras” of the ballet world) in American Ballet Theatre’s Romeo and Juliet. In the following essay, originally written as a chapter in her unpublished, “Coffee Shop Dreams,” she recounts the experience for an engaging behind-the-scenes look at ballet and its legendary stars.

“Bodies, Monks and Mourners, On Stage!”

(Backstage call for Act III “Romeo and Juliet”)

I’m in an elaborate costume on stage in front of 6,000 people, there is a full orchestra playing Prokovief in the pit, my teenaged son, dressed as a Renaissance servant, is standing next to Natalia Makarova, and Mikhail Baryshnikov is watching from the wings. Am I dreaming? No, I’m a ballet mother and a Supernumerary for American Ballet Theatre’s “Romeo and Juliet,” choreographed by Kenneth MacMillan.

The Shrine Auditorium, cavernous, ornate, rarely used except for the Academy Awards, was ABT’s usual home when in L.A. While the company proper was off at a gala fete and fundraiser at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, a motley crew of thirty men and women hoping to make the Super cut lined up for appraisal in the Shrine’s freezing rehearsal hall on a cold Sunday in March, 1985.

We were all types, sizes and ages, not just the “tall, ballet type” advertised for on the bullet board at my son Jason’s ballet school. We took off our jackets and sweaters and lined up according to height in front of a seated panel of three, just like years ago when I auditioned as a dancer.

I had dressed for warmth and comfort not beauty, and I felt strangely vulnerable, fat and naked in the lineup. I’m too old for this, I thought. Immediately I was asked to step forward along with two other middle-aged women. They’re eliminating me at once because I’m not right, not what they want, I thought. The old insecurity and fear of rejection was lurking close to the surface.

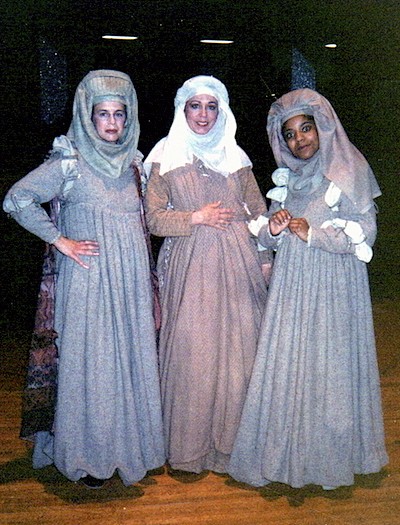

But it was just that we three had been pre-selected to be “Market Ladies” because of our height. At first I was disappointed that I was not to be an “Elegant Lady” (due to my bust size–the first time 36A was ever too large!) Our roles were determined by what costumes we fit, nothing more.

But it was just that we three had been pre-selected to be “Market Ladies” because of our height. At first I was disappointed that I was not to be an “Elegant Lady” (due to my bust size–the first time 36A was ever too large!) Our roles were determined by what costumes we fit, nothing more.

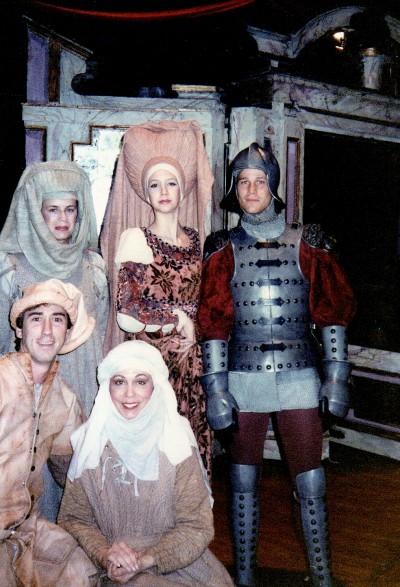

Market Ladies wore different multi-layered costumes weighing perhaps twenty pounds each. Underneath was a full-length heavy petticoat with a ruffle. Then, in my case, a dress of heavy beige upholstery-like fabric with slit sleeves and lacing up the front and back, plus a long tunic of another beige fabric laced up the front and sides. My headdress, of faded-looking beige and violet muslin, had an Arabic flair and a wimple fastening under the chin. Each of us wore similar but differently detailed costumes. Jason was cast as a Green Litter Bearer for the ball in Act I, and a monk in the Capulet tomb in Act III.

Since there was only one professional union dresser, it was necessary for us Supers to help each other in and out of the difficult hooks and laces–no zippers! We formed a costume daisy-chain before and after each act with the dresser at the end. In this way we got our laborious changes down quickly, and I got an amusing snapshot of eight people concentrating hard on lacing each other up.

When the Supers arrived for our first rehearsal, the company class was just winding up. Dancers familiar to us from photographs and the stage looked like typical ballet students in their colorful and eccentric rehearsal clothes. But a sight unfamiliar in a ballet studio was the several animals stationed around the outside of the practice floor, tethered to the barres with leashes.

At that time, there were about twelve dogs and eight cats that traveled with the dancers, and the dogs usually attend class and rehearsals with their owners. There’s even a dog walk-on in “Giselle” and “Swan Lake, so often the larger animals get a chance to be on stage. In the meantime, the pets add love, comfort, and companionship to the dancers’ life on the road. There were so many animals backstage (they were always polite and well-behaved) that a dog and a large bag came to mean “dancer” to the fans at the stage door.

Opening night there was a black-tie reception after the performance in the rehearsal hall for the Friends of ABT–those who contributed substantially. All during dress rehearsal and the performance afterwards, the caterers were setting up. Topiary trees with fairy lights surrounded white tables topped with Cinzano umbrellas around a small dance floor. Festive tents covered the bar areas and the disc jockey’s equipment, which included Italian popular songs for the Romeo & Juliet theme.

There were white flower carts filled with fruits and cheeses, an Italian ice pushcart dispensing zabaglione, chocolate-hazelnut, and wild-blueberry ices in little paper cups, and a long buffet of hot and cold pasta dishes. The preparations went on for hours before and during the performance, and as we hurried back and forth between dressing rooms and the stage, we Supers eyed the food and drink being set out. After the second act the lighted Italian fountain was turned on and we were ready to run over and stick a paper cup under it, hoping it was champagne.

The word went around that the cast was invited to the party and that the Supers were considered part of the cast! This was an unexpected perk to our $10 per performance with free parking, and one we enthusiastically appreciated; by that time we had been in the Shrine for ten hours.

Jason dashed over and grabbed a glass of champagne, and began a conversation with the late principal dancer Patrick Bissell. (“Loved your double cabrioles last night in “Raymonda!”)

But I didn’t know what to do: on the one hand, I love gala parties like this under normal conditions; on the other, I was dressed in a red corduroy jumpsuit and sneakers, not the latest word among the sequin-and-fur set now streaming through the doors from the auditorium.

On the one hand, many of the company dancers were wearing warm-up clothes; On the other, obviously I was not a skinny young company ballet dancer. But I was hungry, thirsty and excited, and so I sidled over and got some champagne (Italian, too, I supposed) and tried to look natural.

I got a plate of pasta and retreated from the glittering garden back over to a circle of metal folding chairs near the Supers’ makeshift dressing rooms, where several Supers were sitting like happy outcasts. Occasionally some of the regal people seated at the white tables inside the circle of lighted ficus trees would turn their heads and glance in our direction, not actually seeing us at all.

Most of the guests were looking for celebrities, of course, and Baryshnikov was there at one of the umbrella tables, as were most of the company dancers.

One of the little boys playing pages ran around asking the dancers to sign his program. Even Jason felt too much a part of the adult world, of the dance world, to ask, though he too would like the souvenirs. Asking for autographs definitely divides the pros from the amateurs. There’s them and then there’s us, and for the duration of “Romeo and Juliet” the illusion of being part of American Ballet Theatre was worth more than autographs of the stars.

People were raving about the Italian ices, and so Jason grabbed me and pulled me over to join the short line in front of the cart. Behind us stood two tall, black-tied men, who assumed we were ABT members and politely asked us questions as if we knew the inside stuff. We ate our ices and faded into the background, and eventually out the stage door into the cold night, trailing stardust and fatigue.

After a few performances we felt like true professional company members as we hurried to sign in, put on our makeup, and prepared to wear our heavy, uncomfortable costumes. It was difficult even to walk in those outfits, and we Market Ladies didn’t mind at all when we were ordered to remove them immediately upon exiting the stage and to put them on again right before Act II. We were not allowed to sit down in them or eat, drink or smoke in them. I wondered about going to the bathroom, but knew it would be impossible to lift those heavy skirts anyway. Luckily the subject never came up for me.

By this time we had learned to quickly dress into our street clothes after coming offstage and sneak into the box right next to the wings. You could only see half of the stage from there, but it was better than standing in the wings where we were in the way. The large orchestra rendering Prokofiev’s powerful score sounded fuller and more immediate from the audience, too.

While onstage, the Supers were to react to the events taking place and join in with the company at certain times, acting and interacting. We Market Ladies had fun mixing with the company on stage, walking around acting naturally, participating in the action first hand. Some of us treated the dancers by sprinkling candy in our market baskets among the plastic products. I put M&M’s in with my grapes.

We didn’t have to feign fear in Act I when the Capulets and the Montagues whipped out their swords and set about killing each other. The stage was crowded with people and the large set, and each performance of the fight got more wild. Twenty men thrusted and parried with real swords (with tiny rubber tips), jumping from landings, leaping through doorways. It was different every time, but always skilled and exciting, and the supers didn’t always know where to stand to get out of their way. As the bodies piled up, the “dead” Capulets and Montagues made jokes and funny faces to those onstage who could see them. They seemed to have a wonderful time.

Nor did I have to pretend sorrow and horror in Act II at the death of Tybalt. I was moved to tears every time Lady Capulet (Georgina Parkinson) rushed down the stairs to Tybalt’s body and seized the sword in a frenzy to attack the remorseful Romeo. Then, convulsed with grief, she sank agonizingly to the floor and rocked the dead Tybalt in her arms to the wailing of French horns, trombones, trumpets and the pounding of the tympani. It was incredibly powerful, indelible. (She always gave him a friendly pat after the curtain fell.)

The last performance was danced by Natalia Makarova and the house was packed, 6,000 people. I couldn’t believe she could be better than the other Juliets I saw, but she was. When she died in the tomb to that poignant minor theme, the audience was on their third Kleenex. Even Martin Bernheimer, the Los Angeles Times’ Critic Terrible at the time, praised her performance, saying that “Makarova IS Juliet!”

Fourteen-year-old Autumn, Jason’s ballet classmate who was playing an Elegant Lady super, pressed a beaded bracelet she had made into Makarova’s hands in the wings after the many curtain calls. Overcome by emotion from the performance, Autumn couldn’t stop her tears. We were all aware that Makarova, at 44, was nearing retirement by her own admission and that we may not see this Juliet again.

Fourteen-year-old Autumn, Jason’s ballet classmate who was playing an Elegant Lady super, pressed a beaded bracelet she had made into Makarova’s hands in the wings after the many curtain calls. Overcome by emotion from the performance, Autumn couldn’t stop her tears. We were all aware that Makarova, at 44, was nearing retirement by her own admission and that we may not see this Juliet again.

In seven performances with seven different casts, including six Romeos and six Juliets, we saw seven different ballets. The choreography was the same and was always danced at a high technical level. But this proved to us the importance of acting, personality, drama, interpretation beyond technique. When Danilo Radojivic’s Mercutio felt his wound in his death scene, I actually “saw” blood on his hand, and I was six feet away from him!

It was “our” last performance, the next ABT “Romeo and Juliet” would be danced in Detroit. Supers were frantically snapping instamatics on the “Cinderella” set which was being assembled near our dressing rooms, as that was the next full-length ballet planned for Los Angeles. We all wanted to see how we looked (no full-length mirrors in the ladies’ dressing room, no mirror at all in the men’s) and to record our moment of glory for scrapbook posterity.

As each costume came off after a scene, it was packed away, and by the end of the ballet, nothing remained of “Romeo and Juliet” in the dressing rooms but huge labeled and sealed cardboard boxes ready for loading onto the trucks.

Most of the supers were anxious to see Superstar Himself, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and since he wasn’t dancing at all during this Los Angeles season, we at first wondered if we would. But we did see him, several times in fact, the first week. (What a shock to see my fifteen-year-old son Jason tower a good three inches over this bigger-than-life man!) Misha was there opening night, the next night for the party, and the night Makarova danced.

That night, during Act III, Jason and the other Supers playing monks were waiting in the wings for their cue, many still transfixed from watching Makarova. The monks were to enter the Capulet Tomb carrying huge lighted candlesticks. Seven monks on the right, eight on the left (the last one being the disguised Romeo sneaking into the tomb), circle the biers and exit up long flights of stairs on each side.

From my seat in the box, I saw the eight left-hand monks enter, but only three right-hand monks–Jason’s side. It looked strange and off-balance, and Romeo’s significance as an extra monk was lost. Jason and three other monks were waiting in the wings for their cue as they had the previous nights, but somehow missed it tonight. Suddenly they saw the lighted candles of the rest of the monks moving across the stage, too late for them to catch up.

“Great, that’s just great!” uttered sarcastically in a Russian accent caused Jason to look to his left and see the great Baryshnikov himself watching this blunder from the wings. Pulling his cowl down over his head, Jason slunk away in shame to take off his robe and to remain anonymous!

Afterwards, Baryshnikov was hounded for autographs inside the stage door by audience members who had found their way backstage. Jason and I made our way through the crowd with our shoulder bags as people stared at us, hoping we were somebody. By the time we got into our cars and were slowly inching by the stage door on Exposition Blvd., we were just in time to see Baryshnikov gleefully carrying a cello case quickly through the crowd that was not on the lookout for a musician. He nearly made a successful escape until the crowd as one body recognized him and took off after him into the parking lot like a swarm of bees. That was the last we, too, saw of the legendary artist during our ABT season. And for this whole two-week wonderful adventure, we had to say a most enthusiastic, Great, just super!

With degrees in English, Dance, and Library Science from UCLA, Cherie Magnus has published many articles in professional journals and magazines. She was the dance critic for the Cerritos News in Orange County, California before moving to Buenos Aires where she taught tango for ten years. Now back at home in Los Angeles, she has published two memoirs: The Church of Tango, and Arabesque: Dancing on the Edge in Los Angeles.

With degrees in English, Dance, and Library Science from UCLA, Cherie Magnus has published many articles in professional journals and magazines. She was the dance critic for the Cerritos News in Orange County, California before moving to Buenos Aires where she taught tango for ten years. Now back at home in Los Angeles, she has published two memoirs: The Church of Tango, and Arabesque: Dancing on the Edge in Los Angeles.

Read more on Facebook: facebook.com/thechurchoftango, facebook.com/arabesquememoir, and on her blog: www.mirasolpress.com

Dance Advantage welcomes guest posts from other dance teachers, students, parents, professionals, or those knowledgeable in related fields. If you are interested in having your article published at Dance Advantage, please see the following info on submitting a guest post. Read posts from guest contributors.