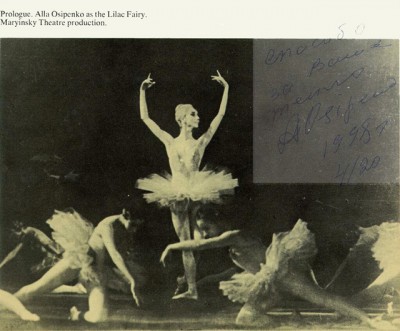

Who is Alla Osipenko?

For many dance students and balletomanes, her name and the name of the Kirov Ballet (now the Mariinsky) calls to mind Soviet dancer defections, the KGB and the Cold War. Osipenko was one of the great Russian ballerinas, a student of the famous Agrippina Vaganova, a partner to Rudolf Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov – and a Kirov star who refused to join the Communist Party, an action which severely limited her travel and exposure to the world. After reading this biography by Joel Lobenthal, a dance historian who conducted over 40 interviews with Osipenko when she was living and working in Hartford, Connecticut in the late 1990s, the reader is left wondering how far her star might have risen had she either defected like her counterparts or acquiesced to the wishes of the Party.

“Alla Osipenko: Beauty and Resistance in Soviet Ballet” meanders at times, often jumping from one event in Osipenko’s life to another with little prelude or seeming connection, yet the ballerina’s life is so mesmerizing that the reader forgives the jumbled mess, which is a testament to Osipenko herself. She sounds like she was a fascinating subject to interview.

Born in Leningrad in 1932, Osipenko lived with her mother, Nina, a woman who pushed her only child into the dance world and insisted that her career come before everything else, including marriage and children, and her grandmother Maria and great-aunt Anna, two women whose lives were devoted to her. Osipenko’s father was imprisoned in Soviet work camps for much of her life, although he was later released and eventually remarried.

Life in the Soviet Union was harsh and often challenging, with resources like food and shelter severely rationed. The dance world, like all of the arts there, was supported – more accurately, controlled – by the government. While dancers were employed like any other workers, they were also expected to represent the Soviet Union in whatever they did. Dancers who did not adhere to a code of conduct and whose morality was questioned, were often punished. For Osipenko, a rebel who bristled at being told what to do, her impulsive nature would lead her into several rash marriages, having a child with a man who was not her husband, and consequently admonitions from the Party.

In 1948, Osipenko began her studies with Vaganova, a teacher who studied with Enrico Cecchetti and brought back his Italian style of dance, fusing it with elements of the French school to come up with her own method of teaching which is called the Vaganova Method and is taught all over the world today. Vaganova was the first “real” teacher in Osipenko’s life, a ballet mistress who was exacting in her technique, expecting only the best from her students. At competitions and auditions, she could be a very strong source of support but privately, she was known to be quite demanding and not given to compliments.

At one such competition in 1949, Osipenko had an experience which would be repeated several times in her career and affect it greatly. After winning a medal (dance awards in Russia and elsewhere are to this day of greater consequence than they are in the United States), the Soviet Ministry of Culture made a pass at her, promising her a career in the Bolshoi Ballet, which was considered a superior company to the Kirov. Her reaction was to slap him. According to Osipenko, he vowed that she would never leave Leningrad “as long as I’m alive.” True to his word, she wasn’t allowed to leave the city for six years. Such was the power of the Party.

One tough dancer: after a devastating performance injury, Osipenko quipped to a friend, “You see I have no Achilles tendon. Sit down with us and let’s…drink champagne.”

In 1950, she joined the Kirov Ballet where she would dance for the next twenty years, have numerous roles created for her, fall in and out of love, and make great friendships, among them Alla Shelest, the second-ranked star in the Kirov at the time. Osipenko and Shelest were unfortunate enough to be dancing at the same time as Natalia Dudinskaya who directed the Kirov and its school with her husband and partner, Konstantin Sergeyev. Dudinskaya was an exceptional dancer but Osipenko and her biographer note that she commanded attention and important roles long past an age when it would have been gracious to allow herself to be replaced, thus keeping both Shelest and Osipenko on a lower rung than they might have had she retired.

After refusing to join the Communist Party, Osipenko told a friend, “When I left that meeting, I realized that my career was just down the drain.”

Two of Osipenko’s partners were Nureyev and Baryshnikov, both of whom defected from the Soviet Union. Nureyev’s defection occurred on the night of her 29th birthday, celebrated in Paris, the night before the company was to travel to London. Instead, Nureyev was nabbed by the KGB who told him he wasn’t going on to London with the company. On the way back, he managed to escape in the Paris airport. Not knowing that he was going to defect, Osipenko offered to go back to Moscow with Nureyev but was told there was nothing that could be done for him. Again, such was the power of the Party.

Other dancers would defect, most notably Natalia Makarova in the 60s and Mikhail Baryshnikov in 1974, but Osipenko remained in Russia. She tried to resign from the company on her own terms but they refused to accept her resignation until it suited them and until they could be sure she wouldn’t defect. Eventually, she was allowed to leave; her final performance for the Kirov was filmed for television, but in front of an empty audience, save for her fellow ballerinas. It was an anti-climactic finale for a fruitful and astonishing decades-long career.

In 1971, she and her husband/partner John Markovsky left Russia to work for Leonid Jacobson’s Choreographic Miniatures Company as well as Boris Eifman’s Theatre of Contemporary Ballet, with Osipenko eventually, in the late 1990s, landing in Hartford, Connecticut to teach for the now-defunct Hartford Ballet. Following the death of her son, Ivan, however, she found herself yearning to return to Russia, which she did in 2000.

Lobenthal’s biography is an enthralling account of a unique personality in dance, a ballerina who was ahead of her time.

Leigh Purtill is a ballet instructor and choreographer in Los Angeles where she lives with her husband and charming poodle. She received her master’s degree in Film Production from Boston University and her bachelor’s in Anthropology and Dance from Mount Holyoke College. She is the author of four young adult novels from Penguin and HarperCollins. She is the artistic director of the Leigh Purtill Ballet Company, a nonprofit amateur ballet company for adults and she teaches ballet and jazz to adults both in person and online, Leigh Purtill Ballet. Read Leigh’s posts.