Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! debuted to instant success in 1943. In terms of dancing, it was a game change for Broadway musicals— its “Dream Ballet” contributed to the drama by advancing and enriching the plot. Previously, dance scenes in musicals had usually been “filler” unrelated to the story. The choreographer was Agnes de Mille and her road to Oklahoma! was many unconventional years in the making…

Early Inspiration

Anna Pavlova, the iconic Russian ballet dancer, was one of de Mille’s early dance inspirations. When de Mille was twelve, she saw the legend perform live and was forever changed. She later remarked that the experience “burned in a single afternoon a path over which I could never retrace my steps”. [1]

De Mille had desired to take dance lessons since the age of five, but was not allowed to until she was fourteen. Even then, she was not permitted to practice for more than forty-five minutes a day. Her parents were skeptical of the activity, believing it lacked intelligence and propriety.

De Mille understandably struggled with technique and famously admitted she was a “perfectly rotten dancer”. Furthermore, she received the dreaded verdict that her body type was not suited for the art form. She temporarily gave up lessons to attend UCLA and earn an English degree. But she in no way gave up on her dancing dreams.

Agnes and Martha

After graduation, she started a journey into choreography. She moved to New York and began a lifelong friendship with modern dance pioneer Martha Graham. She also devised her own solo concerts – creating dances, arranging the music, and designing the costumes. Most of these were pantomime/dance character sketches. One of the characters she portrayed was a cowgirl who, many years later, would be the inspiration for the heroine of her first major choreographic success. These early performances received favorable reviews from critics, but proved a financial loss.

After New York, she went to London where she studied dance under Marie Rambert and trained alongside British choreographer Antony Tudor. In 1937, she performed in Tudor’s premiere of Dark Elegies, a ballet about a rural European community mourning the loss of their children. Tudor’s works have been described as “psychological dance dramas” and they impacted de Mille’s own style of choreography.

Dark Elegies Excerpt (Full work: https://vimeo.com/104872233)

Rodeo (roh-DAY-oh)

Then, in 1940, at age 35, de Mille was offered a job to choreograph for a newly-formed company in New York called Ballet Theatre- later known as American Ballet Theatre. But she did not have have a significant breakthrough until Rodeo- a work commissioned by the touring company Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1942 as a patriotic homage to America in the midst of World War II.

For Rodeo, de Mille created a romantic, Cinderella-like story about a cowgirl whose “fairy godmother” is her own persevering, can-do spirit. At first, the cowgirl desperately tries to attract the attention of the local cowboys by meticulously imitating them- even down to her choice of clothing. When this fails, she cries a bit, then changes strategy by giving herself a makeover and going to a hoedown. She not only gains a suitor, but immediately becomes the belle of the ball.

Rodeo’s choreography incorporates square dancing, tap, modern dance, and naturalistic gestures based on movements such as horseback riding and roping. The ballet was a hit. On opening night, there were twenty-two curtain calls and de Mille, who danced the role of the cowgirl herself, received an all-American bouquet of corn wrapped in red, white, and blue ribbons.

Rodeo Excerpt

Oklahoma!

It was de Mille’s success with Rodeo that led to her being hired to choreograph Oklahoma!

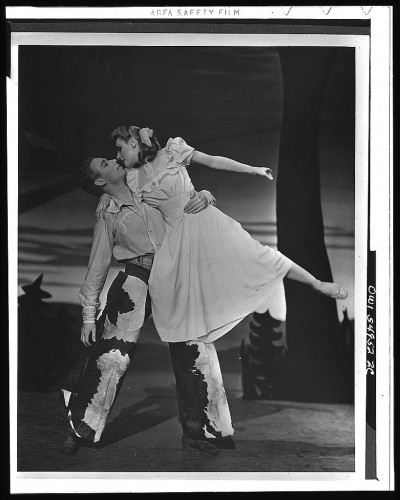

The musical’s seminal dance sequence “The Dream Ballet” or “Laurey Makes Up Her Mind”, explores the female lead’s tension of deciding between two suitors: the good-hearted Curly and the sinister-yet-intriguing Jud. It begins with a joyous, romantic pas de deux by Laurey and Curly, followed by preparations for their intended wedding. But the dream quickly turns into nightmare when Laurey arrives at the church to discover that her groom is actually Jud. She then encounters Jud’s true nature as she comes face-to-face with his seedy saloon associates and witnesses him kill Curly in a fight. This vision, of course, reveals that Jud, the initially exciting “bad boy”, would be a terrible match for her.

“The Dream Ballet” is an accumulation of de Mille’s diverse influences: ballet, modern dance, Tudor’s “psychological dance drama”, and her experience with incorporating American folk themes into choreography. The New York Times pronounced “The Dream Ballet” a “first-rate work of art” and declared that it achieved what “many a somber problem play” failed to convey “after several hours of grim dialogue”.

“The Dream Ballet” from the 1955 film version of Oklahoma!

Ironically, the rave reviews of Oklahoma! inspired serious doubts in de Mille. She felt she had produced far better choreography in other works. She became conflicted about her artistic judgment. In her turmoil, she turned to Martha Graham. Graham’s advice was to just continue creating and not to get bogged down by weighing her opinions against the critics. She explained:

There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is nor how valuable nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open.

De Mille did indeed “keep the channel open” and experienced many more successes- and failures- in her creative life. In words that have become oft-quoted in the dance community, she summarized the necessary sense of daring and its accompanying insecurities that are inherent in the artistic path, “The artist never entirely knows. We guess. We may be wrong, but we take leap after leap in the dark.”

What inspires you to “leap in the dark”? How do you “keep the channel open” during doubt?

______________________________________

[1] On Wings of Joy by Trudy Garfunkel, 1994, p. 148

Rachel Hellwig is a dance writer/editor/blogger from Birmingham, Alabama. She enjoys taking ballet classes, reading about dance, and attending live performances of ballet and classical music. She blogs at Clara’s Coffee Break. Read Rachel’s posts.