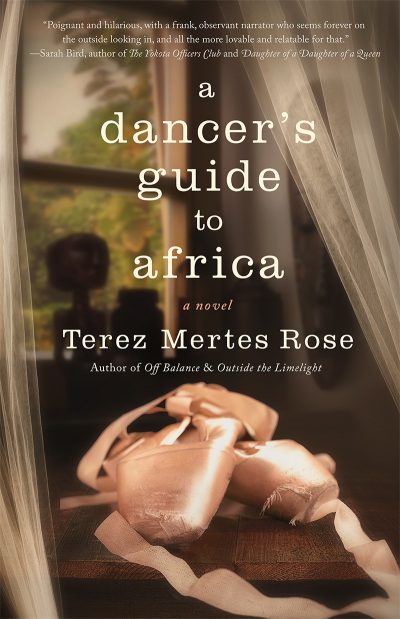

In Terez Mertes Rose’s latest novel, a recent college grad, feeling lost and dejected after her older sister becomes engaged to her ex-boyfriend, decides to join the Peace Corps and travel to Africa. Fiona’s life changes in ways she couldn’t have imagined, thanks to the people she meets and the dance form she discovers.

From the author’s website:

Fiona Garvey, ballet dancer and new college graduate, is desperate to escape her sister’s betrayal and a failed relationship. Vowing to restart as far from home as possible, she accepts a two-year teaching position with the Peace Corps in Africa. It’s a role she’s sure she can perform. But in no time, Fiona realizes she’s traded her problems in Omaha for bigger ones in Gabon, a country as beautiful as it is filled with contradictions.

Emotionally derailed by Christophe, a charismatic and privileged Gabonese man who can teach her to let go of her inhibitions but can’t commit to anything more, threatened by an overly familiar student with a menacing fixation on her, and drawn into the compelling but potentially dangerous local dance ceremonies, Fiona finds herself at increasing risk. And when matters come to a shocking head, she must reach inside herself, find her dancer’s power, and fight back.

Set in the 1980s, A Dancer’s Guide to Africa follows Fiona from Nebraska to Gabon, from naive college student to maturing adult, from victim to victor.

Anyone who has ever traveled abroad knows what it’s like to be a stranger in a strange land. As a tourist, you accept that people in the foreign country see you as the foreigner and it’s pretty easy to accept since you’re only visiting for a short time. But what about when you move to a foreign country to live and work? What if you don’t speak much of the language, don’t look like the people who live there, and don’t understand the culture?

Fiona serves as our eyes in a land that is probably unknown to most of Terez Mertes Rose’s usual readers. She asks the questions for us and makes the mistakes we would likely make too, including assumptions of monogamy in romantic relationships. Above and beyond the day-to-day activities Fiona engages in as a teacher of English to African students, her attempts to understand romance among the Gabonese is the most challenging.

Through the lens of a typical American woman, Fiona assumes men and women in Africa conduct intimate relationships in a monogamous fashion. When she falls for Christophe, a handsome and well-connected Gabonese man, she is shocked to discover he has other girlfriends, including one he plans to marry. She becomes petulant and jealous, making snide comments about the other women in Christophe’s life – much to the disdain of her friends who tell her she is being very naive. Just because the rest of the world doesn’t conform to your view, they tell her, doesn’t mean their ways are invalid.

One of the unique aspects of this novel is Rose’s ability to allow Fiona to show her ugly side to readers. It’s not attractive to hear someone whine about a boyfriend. It’s not charming to hear a person constantly say, “No, I can’t,” instead of, “Yes, I’ll try.” The writer exposes the raw side of Fiona’s inner monologue throughout her time in the Peace Corps, but then forces her to grow up. Fiona, through a dance form that she had previously insisted she couldn’t even attempt, discovers a strength she didn’t know she had, a power that is both mystical and mystifying. When she is faced with a terrifying situation, she defends herself in a physical and emotional way she hadn’t experienced before. As a reader, it’s gratifying to witness the transformation.

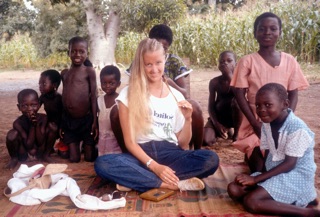

I had an opportunity to interview Terez for this review. Having never been to Africa myself (although it’s a place I hope to visit in the near future!), I was excited to hear about her experiences there first-hand and to find out how they influenced this book.

Leigh Purtill for Dance Advantage: Welcome, Terez! And thank you for answering my many, many questions! First of all, Fiona, your main character, is a Peace Corps worker in Africa. Did that come from your own experience?

Terez Mertes Rose: It did! Although the circumstances around my joining the Peace Corps were different from Fiona’s. My older brother had served in the Peace Corps six years earlier. I’d thought it was such a dramatic, noble thing to do, and during college years, I set my sights on doing it upon graduation. I was in a dance company through my college years and loved ballet like nothing else, but reality whispered to me that I didn’t have the chops to go professional, and I really had

to consider a future outside ballet. I contacted the Peace Corps early on and followed their suggestions on how to make myself an attractive candidate for the job, and it all played out as I’d hoped. It broke my heart to leave ballet and my dance company behind, but it was the right choice.

LP: The book is set in the 80s which is a very specific time and place for our culture. Did you have to do a lot of research to make it authentic? Did you remember everything that was going on then?

TMR: Indeed, I have very specific memories of what it was like to be a Peace Corps volunteer in the 80’s. (My own years were 1985-87; the story takes place 1988-90.) I wanted to keep it in roughly the same time period because conditions change. The AIDS epidemic became a much bigger deal in Africa in the 1990s. There was political unrest in Gabon and its capital city, Libreville, in 1990 (which technically was during Fiona’s time, but I chose not to use any of that in my story – gotta love fiction writing!). Setting the story in 1988 meant fewer logistics errors.

LP: Did you ever consider writing this as a memoir?

TMR: Nope. My own experiences seemed less glamorous than Fiona’s. I discovered only there in Africa that I was a huge introvert. At my post, I kept to myself probably more than I should have, losing myself in books and writing in my journal a lot. Fiona just flings herself out there and gets into trouble. (Fictionalizing an experience is so much more fun!) Initially I did try to pound out memoir material—I was purely a nonfiction writer at the time—but the end result bored even me. One day I had a “what if…?” moment, created Christophe and this cross-cultural romantic conflict, and wow, did the story take off. The novel just wrote itself, 100,000 words in ten short weeks. It was an amazing experience, just waiting for the right fictional character to show up and make it happen.

LP: It was a very interesting creative choice to keep the entire story within Africa. Although we get glimpses of what is happening in Fiona’s sister’s life, we immerse ourselves in Africa. Can you talk about that insularity?

TMR: I think, psychically, I wanted to immerse myself wholly back in this place where I’d once lived. It plunged me into another world, which I just loved. That said, the first few drafts of the novel had much more reference to home, and included letters between Fiona and her sister. I was advised by more than one beta reader to drop those, so I did. And in the final draft, when the word count was well over 100,000, I had to make tough choices, and out went a few flashback scenes set in Omaha. I miss them, but the story is tighter—and shorter—without them.

LP: Was there material you found difficult to write about? The cultural differences for instance?

TMR: Actually, I loved exploring all the cultural differences through writing. It was a great opportunity for me to process what I’d been too young and naïve to see clearly, back in 1985. (Although Fiona is NOT me, I have to admit that we are very similar in this department.) What I found very difficult to write about was the malevolent character whose intentions toward Fiona were sinister. The penultimate chapter was just awful to work on. Violence repels me. But I think it’s a stronger story for coaxing out that aspect of the culture, because violence exists there, and violence toward women exists there.

LP: Did you ever go back to Africa? Do you keep in touch with anyone?

TMR: I never went back to Africa—it’s a pretty complicated process to travel through Central and equatorial Africa, particularly Gabon, where I served as a volunteer. Visas are hard to obtain, the travel is costly and time-consuming, and for quite some time, leisure travel through that part of the continent hardly existed. I’ve kept in touch with fellow Peace Corps volunteers, a few Gabonese, a few French expatriates and fellow teachers, but contact has mostly faded away as letter-writing is replaced by texting and Facebook. (Not to mention that thirty years has passed since I was there.) The sad truth is, some of my Gabonese friends have died already. Life expectancies are so much shorter there. It’s sobering and humbling.

LP: Was there anything you left out of the story because you couldn’t find a place for it?

TMR: Tons. Two years’ worth of vivid impressions add up to a lot. I had to pull out an entire story thread that related to AIDS and the way it was just starting to show up in Central Africa in the ‘80s (amid a good deal of official denial in Gabon). And I could have written another novel simply on the political and socio-economic climate of the country. Or tell the story from an environmentalist’s perspective. Or a Peace Corps administrator’s point of view. I have a hunch

there might be a second Africa novel within me. Carmen, Fiona’s best friend in the story, has assured me she’ll stick around and be the narrator for the next one. I might take her up on that.

LP: I loved how Fiona was so naive, so black-and-white about dance when she first arrived but gradually saw how she could do African dance if she allowed herself to. Did you see that as a metaphor for our racial and cultural divide?

TMR: You know, I love the metaphor idea, and it would make me feel more noble to say, “yes, definitely!” but the truth is, no, I saw the story as simply being a young adult’s internal journey and coming of age. I wanted to share how fish-out-of-water an American can feel in a foreign culture, and the difference in a Peace Corps volunteer in their first six months, compared to their later months, which is pretty significant. The fun thing about the Peace Corps, too, is that by the end, you feel so comfortable, so acclimated to the racial and cultural differences, you don’t see yourself as such an outsider. You’re simply another resident in your town, with local colleagues and friends who have problems much like yours (or so you think at the time). Fiona really “found herself,” there in Gabon. I hate to be the one to tell her that readjustment back in the U.S. is the really hard part, but that’s the truth. Observing racial divisions back in the U.S. upon my return was a shocking experience. I wasn’t ready for the “us” and “them” feeling that popped up around me in my native Kansas City.

LP: How do you feel an experience like this in today’s climate might be different from what Fiona experienced in the 80s?

TMR: Great question! I think there is a certainly timeless sense in tradition-bound cultures; I’m inclined to think that in rural Gabon, the locals eat precisely the same thing now that they ate when Fiona was there, which was surely the same thing their grandparents and their grandparents ate in their generation. But the advent of better telecommunications and cell phones and internet would make a HUGE difference. I see blogs online that are composed by Peace Corps volunteers out at their rural posts, and it blows my mind to consider how that would eradicate the feeling of isolation entirely. Getting emails from friends and family? Phone calls any day of the year? Skyping?! I remember reading one volunteer’s comment that “you don’t know real loneliness until you’ve hung up from Skyping with your family.” And I thought, “Um, I knew real loneliness from only speaking to my family four times in a two-year period and that was only when I was in the capital city.” But now that I consider it, maybe it’s even harder for volunteers now, to get this tantalizing glimpse of their own culture, only to have it disappear once the connection ended (or dropped out). Likely, the loneliness blooms anew and you have to battle it all over again. Whereas Fiona, like myself, became immersed in the culture and didn’t leave it until the end of her two-year service. And of course politically, with more democracies in the world – and paradoxically, more unrest, more upheaval as a result – it would be a different experience. I think what is occurring now, as well, is the way educated people from these cultures are starting to question these long-held traditions and superstitions, which serve to harm others (most frequently women). And there are likely an equal amount of people (read: tradition-minded men) who do NOT want anything to change. Fiona was stared at and rudely

questioned for being a single women living on her own in Africa. I think that still would happen, even today.

LP: Do you feel this experience affected your relationship to ballet? To dance?

TMR: Not during my own Peace Corps experience. Back then, I faithfully did a 30-minute barre in my home, twice a week, for the entire two years. It was my grounding point, the umbilical cord to my past. Ironically, it was upon my return, when it became necessary to juggle ballet with a career, a demanding full-time job, that my love affair with dance began to wane. At one point, taking classes became more an obligation than a joy. When I changed jobs and moved cross-country, I told myself I was done with dance. Silly me! The experience of writing this story, fifteen years after my return from Africa, reignited my love for dance, and actually prompted me to take a weekly African dance class.

LP: Is there anything you’d like readers to know, anything you feel could help them or encourage them to explore?

TMR: Join the Peace Corps! [laughing] Just kidding. Or maybe not. There’s something called Peace Corps Response that is short term and utilizes (older) professionals for very specific jobs. 6 to 12 week volunteer opportunities overseas abound these days. It’s such formative stuff: the culture, the people, the humbling nature of being a foreigner for longer than just a vacation, the confusion you feel after months into your job when you realize that what you see on the surface is not at all what is going on deeper within the culture or its people. It’s like an onion, living in Africa. You peel back layer after layer, and there are always many, many more layers. And since I know most people can’t just “run off to Africa,” I wrote this story to share with armchair adventurers, incorporating the grit, the unforeseen challenges, the bafflement and reverence, in the hopes that they come to “see” the Africa I saw. In some ways I wrote this as a love letter to Africa, one that I want to share with the world. The more all people can relate to or simply learn about foreign cultures, African or otherwise, really understand them at the personal level, the better this world will be.

Terez Mertes Rose is a writer, former Peace Corps volunteer and ballet dancer whose work has appeared in the Crab Orchard Review, Women Who Eat (Seal Press), A Woman’s Europe (Travelers’ Tales), the Philadelphia Inquirer and the San Jose Mercury News. She is the author of Off Balance and Outside the Limelight, Books 1 and 2 of the Ballet Theatre Chronicles (Classical Girl Press, 2015, 2016). She reviews dance performances for Bachtrack.com and blogs about ballet and classical music at The Classical Girl (www.theclassicalgirl.com). She makes her home in the Santa Cruz Mountains with her husband and son.

**

Author Links:

Blog: www.theclassicalgirl.com

Website: www.terezrose.com

Purchase: “A Dancer’s Guide to Africa” on Amazon

Facebook: facebook.com/TheClassicalGirl/

Twitter: @classicalgrrl

Leigh Purtill is a ballet instructor and choreographer in Los Angeles where she lives with her husband and charming poodle. She received her master’s degree in Film Production from Boston University and her bachelor’s in Anthropology and Dance from Mount Holyoke College. She is the author of four young adult novels from Penguin and HarperCollins. She is the artistic director of the Leigh Purtill Ballet Company, a nonprofit amateur ballet company for adults and she teaches ballet and jazz to adults both in person and online, Leigh Purtill Ballet. Read Leigh’s posts.