Correcting Teacher Corrections

As teachers, we have the challenge of framing our corrections in a way that is concise, accurate, and effective. Certain catch phrases, quibbles and mantras have been told to us by our teachers, and, as we became teachers we use them in our turn. I’ve been thinking a lot about correcting students and how effective some of the standard dance teacher vernacular really is. One such correction is “Get up on your leg”

“Get up on your leg”…

Teachers have a habit of saying this when students are “sinking” into their supporting leg while balanced on one leg. A lot of dancers do, in fact, demonstrate this, but is “get up on your leg” the best way to correct it?

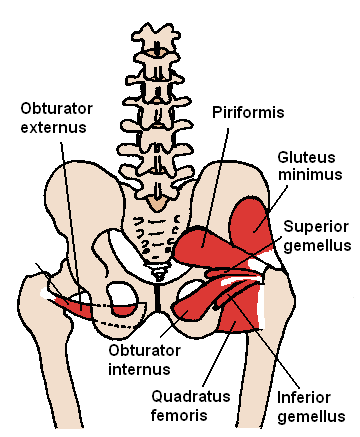

When a dancer is supporting the body weight on one leg, either standing or en relevé, there is a tendency to release the gluteal muscles (maximus, medius and minimus) and abductors (tensor fasciae latae, piriformis, obturators, gemelli and sartorius). Whether this is due to laziness or lack of strength isn’t quite the point, but ultimately lax muscles that are meant to support the hip allow it to fall away from the midline and sink.

The big problem I have with saying “get up on your leg” is that students often overcompensate by raising their working hip. Then you tell them to drop their hip, and they overcompensate by sinking into their supporting hip again. Then you tell them to get up on their leg…. it’s a vicious cycle.

What To Do

Sinking in the hip is an error many student dancers (and, let’s face it, some professionals) experience that takes a while to correct, as it is likely the result of weak muscles in the ankle and hip (3) (specifically gluteus medius and minimus; tensor fascilae latae; and posterior tibialis, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus).

While some corrections are given due to negligence or laziness on the part of the dancer, if a student is continually being asked to get on their leg and simply can’t seem to maintain the proper alignment, try encouraging them to strengthen their abductors. Though other muscle groups are implicated in a sinking hip, the abductors are not especially targeted by ballet technique, which makes them a likely culprit. Working with the feet in a parallel position (by taking a jazz or _w_therab_2.gif) modern class) can strengthen these muscles-especially exercises that extend the leg to the side in parallel.

modern class) can strengthen these muscles-especially exercises that extend the leg to the side in parallel.

Use a theraband wrapped around the legs, for dancers who can’t “get up on their leg”. Although it is a trademark of dancers to walk through their daily lives in turnout, simply making it a point to walk in parallel can help keep these muscles active. For dancers interested in Pilates, the hip abductor series is a great tool for this problem.

Related Injury

Weak hip abductors can also be implicated in a couple of common dance injuries. Runners with weak abductors experience increased knee abduction during the stance phase (which is essentially equivalent to dance positions placing the body weight on the supporting leg) (4). In this case the femur is not stabilizing the hip and is not fully supported at the knee joint, causing abduction of the knee and the potential for the femur to rub against the patella (5). Patellofemoral stress syndrome has been also correlated with weak hip abductors as a result of this movement within the knee joint (2).

What To Say

So if “get on your leg” doesn’t work, what do you say to a dancer who sinks in her supporting hip?

As I’m sure you already know, it depends on the student.

Some students respond better to metaphors that will encourage them to activate the muscles of the hip and ankle:

“Drive your leg into the ground like you are mounted in cement…”

or to engage the gluts and lower abdominals:

“Lift the upper body and perch it on to of the legs like a bird resting on a thin branch…”

Some students might respond better to physical manipulation. Back up your adjustments with verbal cues:

“Lift the lower tummy; feel a pinch under your bottom; engage your hip and feel it wrap around to your back…”

What do YOU say to a student who sinks in her hip?

References:

- Calais-Gemain, B. (1993). Anatomy of Movement

. Seattle: Eastland Press.

- Dierks, T. A., Manal, K. T., Hamill, I. S. (2008). Proximal and distal influences on hip and knee kinematics in runners with patellofemoral pain during a prolonged run. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 38, 448-456.

- Grieg, V. (1994). Inside Ballet Technique: Separating Anatomical Fact from Fiction in the Ballet Class

. Hightstown, NJ: Princeton Book Company.

- Heinert, B. L., Kernozek, T. W., Greany, J. F. & Fater, D. C. (2008). Hip abductor weakness and lower extremity kinematics during running. J Sports Rehabil 17, 243-256.

- Schamberger, W. (2002). The malalignment syndrome. Oxford: Churchill Livingstone, 344-346.

Lauren Warnecke is a freelance writer and editor, focused on dance and cultural criticism in Chicago and across the Midwest. Lauren is the dance critic for the Chicago Tribune, editor of See Chicago Dance, and founder/editor of Art Intercepts, with bylines in Chicago Magazine, Milwaukee Magazine, St. Louis Magazine and Dance Media publications, among others. Holding degrees in dance and kinesiology, Lauren is an instructor of dance and exercise science at Loyola University Chicago. Read Lauren’s posts.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=1f08385a-193e-442b-9816-5eed27e75884)